For many years it has been generally held that the old parish of Nonington had within its bounds the greater parts of, if not all, of the Domesday listed manors of Eswalt, Essewelle and Soles running roughly north to south through its centre with substantial holdings of the Manor of Wingham on its western and eastern sides. These Wingham holdings consisted of parts of Oxenden [Oxney] and Acol [Acholt] manors, Curleswood Park, Ratling, Old Court, and Nonington North and South to the west and Kittington to the east.

However, over the last year or so it has become more obvious to me that here was another manor with a large holding of land within the old parish of Nonington, namely Hartanger, which has also been recorded over the centuries since the Domesday Survey of 1086 as Hertanger, Hartange or Hartangre.

This ancient manor appears to have been centred on the present Church Farm in the adjoining parish of Barfreston and to have included a substantial area of land lying mainly on the eastern side of the dry valley that forms the majority of the present Fredville Park that had previously been attributed to the manor of Fredville.

Hartanger may have originally meant the deer wood, deriving its name from the from the Old English heorot [Middle English, hert], meaning a deer, and hangar, also hanger or hangre, meaning a wooded slope. The probable original name in full would have been more descriptive, meaning something like “the wooded slope where the deer are to be found”. In pre-Norman times these would have been roe deer, a mainly woodland dwelling species, as the larger fallow deer was not introduced into England until after the Norman Conquest when it was brought over and released into aristocratic hunting preserves.

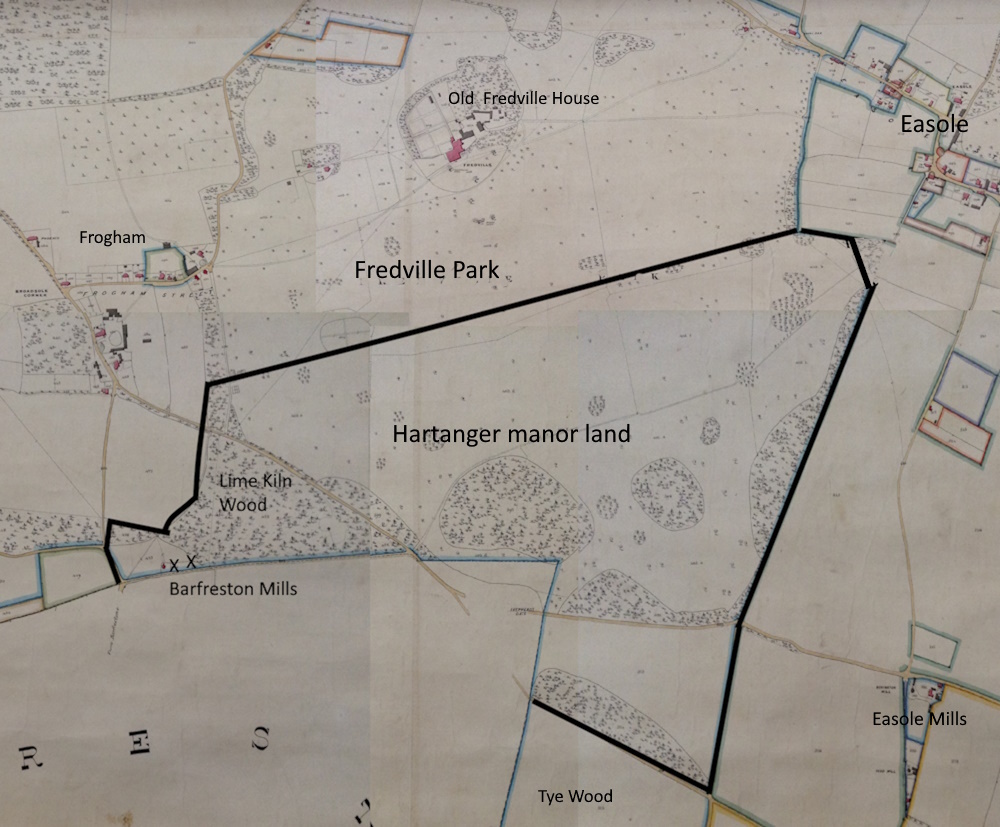

Its location on the eastern slope of the dry valley containing Fredville Park adds credence to this as Fredville itself most likely derives its name from frith or frid, meaning an area of woodland or scrubland. The woodland, including the present Lime Kiln Wood between Frogham and Barfreston, would also have extended eastwards over the crest of the hill and down the western slope of the neighbouring dry valley to meet up with what in later centuries was know as Tye Wood.

Tye is derived from Old English teag, meaning a small enclosure, but the 13th century or earlier in Kent it had come to mean a common pasture. The woodland was grubbed up in the early 1960’s, and nothing now remains of the wood other than the name.

The Hartanger manor lands within the old Parish of Nonington. An extract from the 1859 Poor Law Commissioners map of Nonington.

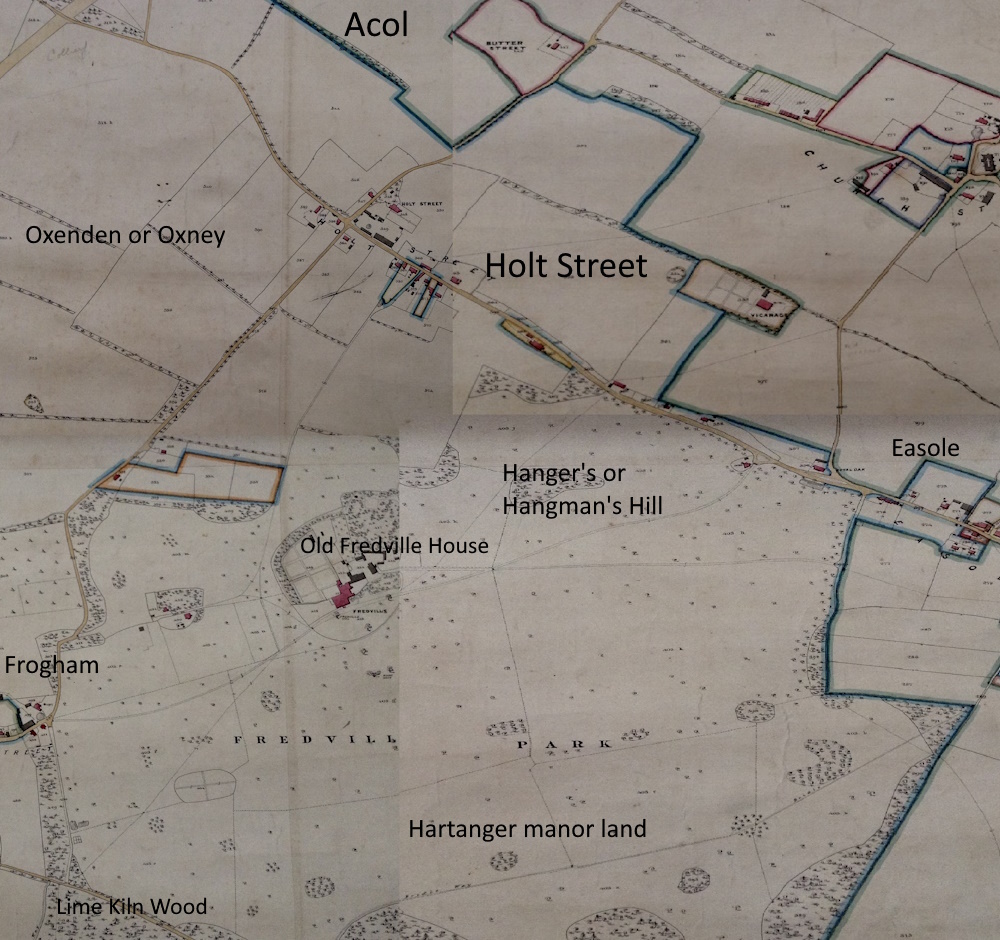

In the adjoining dry valley to the west of Fredville Park lies the present Nonington cricket ground and the slope at the southern end of the ground is known as Hangers Hill, sometimes Hangman’s Hill, which also appears to derive from its name from the OE hangar.

Along the western slope of this same valley is the hamlet of Holt Street, which derives its name from holt meaning wood in Old English. Immediately adjoining Holt Street to the south-west is Acholt, oak wood, and adjoining on the south is Oxenden, the woodland clearing for grazing oxen or cattle.

Hartanger, Fredville, Holt Street and Acol. An extract from the 1859 Poor Law Commissioners map of Nonington.

At the time of the Domesday Survey of 1086 the Manor of Hertange, as Hartanger was then spelt, was part of the extensive land holdings of Odo, Bishop of Bayeaux and a half-brother of King William I of England, now better known as William the Conquerer. The survey records Hertange as follows:

“Radulf, son of Robert, holds of the bishop Hertange. It was taxed at one suling. The arable land is In demesne there is one carucate, and five villeins, with two borderers, having two carucates. In the time of king Edward the Confessor, it was worth forty shillings, and afterwards ten shillings, now sixty shillings. Eddid held it of king Edward”.

[ “Ralph, son of Robert holds Hartanger from the Bishop. It answers for 1 sulung. Land for….In lordship 1 plough. 5 villagers with 2 small holders have 2 ploughs. Value before 1066, 40s [shillings]; later 10s; now 60s. Edith held it from King Edward”.

[Translation of the original entry for Hertange from Philmore, Kent reference: 5,202.]]

Four years later Odo rebelled against King William and consequently had his English holdings confiscated by the Crown which retained possession of the manor of Hertanger for an unknown period of time. Eventually, what had become the knight’s fee of Hartanger was given by the Crown to Hugh de Port and it became a part of the Barony of Port which had a duty to perform Castleward at Dover Castle.

A number of the Castleward baronies consisting of knight’s fees mainly in Kent were formed for the purpose of garrisoning of Dover Castle on a shared basis. At the outset holders of a knight’s fee were liable to an annual fixed period of garrison duty at Dover Castle but as it became more common for knight’s fees to be bought and held by members of a growing class of wealthy merchants with no military prowess this obligation to perform garrison duty gradually transmuted into a regular cash payment to finance the employment of professional soldiers. By the early 1200’s the manor was in the possession of a family who took their name from their manor. In 1234 there is a record of a William de Hartanger witnessing a documents and eight years later the 1242-43 “Aid for the King’s crossing the sea to Gascony” recorded that William de Herthangre, most likely the aforementioned William, but possibly a son or other heir of the same name, held one knight’s fee at Herthangre from Simon fiz Adam [FitzAdam], who in his turn held it from Walter fiz Robert [FitzRobert], who held it from the King.

Some five years later in 1247 a William de Hartanger was witness to a land deed and once again it is not clear whether this was the original William or a successor of the same name. The custom of father’s from knightly and aristocratic families of naming their eldest sons after themselves does not make it easy to identify who did what, and to whom.

In 1268 a William of Herthanger, along with Ralph Colkyn of Esole and eighteen other members of the local gentry, was accused of crimes connected to the massacre of the Jews in Canterbury that had occurred in April of 1264. This William was most likely the son or grand-son of the original William, and when he and the other defendants were eventually bought to trial in 1270 it was found that here was no case for them to answer.

Presumably it was the innocent above mentioned William de Herthangr’ who was recorded in the Kent Hundred Rolls of 1274-75 as holding one [knight’s] fee in Herthangr’ from Simon, son of Adam [Simon FitzAdam], either the Simon referred to in the 1242-43 Aid for the King’s crossing the sea to Gascony or a descendant of the same name, who in turn held it from the King. William is also recorded as owing 20s at Dover Castle, as Hartanger was a constituent part of the Barony of Port, one of the Baronies responsible for Castleward at Dover, which made William liable for a fixed regular payment towards the garrisoning of Dover Castle.

Possession of Hartanger remained with the family of that name until the early 1300’s when the manor came by purchase, possibly by Thomas Perot, into the possession of the Perot family who then also held the nearby knight’s fee and manor of Knowlton.

Thomas Perot, the presumed purchaser of Hartanger died possessed of the manor in 1331 and appears to have been succeeded by Henry Perot, after who references to the Perot in connection with Hartanger are scarce.

In 1346 aids and scutages for getting the king’s eldest son made a knight there is a record of Richard, son of Richard Retlyng’, Henric Perot of Berfrayston’, and Johan Judeleye being jointly being responsible for one knight’s fee that Reginald de Thondresle held at Hertangre from the earl of Arundel. They would therefore all hold one third part of the knight’s fee.

The same document also records Richard, son of Richard Retlyng’, as holding a fourth part of the knight’s fee of Essewelle in Nonington, where the family also held land and property.

On the death of Richard de Retlyng’ senior in 1349 an inquisition was held to assess the extent of his debts and how they would be settled. Reference was made to Richard holding one hundred acres of land and a windmill in Barfreston, most likely a mill on the site of the later Barfreston mills.

The date of the death of the last male Perot of Hartanger is not known, but during the later part of the 1300’s or early in the 1400’s the heiress of the Perot family who had holdings in Knowlton and Hartanger married a member of the Langley family from Warwickshire, thus transferring her inheritance, which included a third part of the knight’s fee of Hartanger, to the Langley family.

William Langley of Knowlton was in possession of one third part the manor of Hartanger in 1411 but little else is known of the family or their affairs until the 1480’s .

In 1428 Sir Thomas Broun, also Browne, came into the possession of “the manor of Egethorne”, and “lands, rents and services in Egethorne, Kyngeston, Beram, Nonyngton, Asshe, Staple, Berfreyston, Wodnesbarwe, Goodneston, Adesham, Wymelyngwelde, Dele and Siberdeswelde”.

[Eythorne, Kingston, Barham, Nonington, Ash, Staple, Barfreston, Woodnesborough, Goodneston, Adisham, Womenswold, Deal and Shepherdswell].

Amongst these acquisitions was a part of the knight’s fee of Hartanger along with land and the afore mentioned windmill at Barfreston.

In 1448 Sir Thomas obtained the grant to hold an annual fair in Eythorne on 1st August, the feast day of St. Peter Ad Vincula [St. Peter in Chains], and another grant for an annual fair at the nearby village of Wimlingswold, now Womenswold, which was initially to be held on 20th July, the feast of St. Margaret the Virgin , but was later held annually on May Day.

Later in 1448 Sir Thomas was granted a licence to crenelate his manor house at Egethorne, now Eythorne Court. This was something only those truly in favour were allowed to do and it meant he could enclose and fortify his manor house with a wall and a moat.

Sir Thomas Browne was the son of a wealthy London merchant and through an advantageous marriage to a descendant of Richard Fitzalan, Earl of Arundel and Surrey he became a very well connected and very wealthy land-owner. Amongst the posts he held was Chancellor of the Exchequer and Treasurer of the Household to King Henry VI, for which he was knighted, and he also served as MP for Dover and later for Kent. A staunch Lancastrian Sir Thomas was loyal to King Henry VI and the Lancastrian cause after 1453 when the king’s unstable mental condition led to mounting tension between Queen Margaret and Richard, Duke of York, as they both maneuvered to gain control of the kingdom’s government. This rivalry resulted in the outbreak of civil war in 1455 which eventually resulted in the leading Yorkists fleeing the country in 1459. The Duke of York fled to Ireland, and the Earls of Warwick and Salisbury crossed the Channel to Calais, where Warwick had been appointed Constable in 1456.

On 26th June, 1460, the exiled Yorkist Earls of Warwick and Salisbury landed at Sandwich and the men of Kent rose to join them. The Yorkist forces headed to London where the citizens opened the gates to them on 2nd July, but the Tower of London remained in Lancastrian hands and was besieged by a small Yorkist force left behind whilst the main Lancastrian army headed for the Midlands to confront King Henry VI and his supporting army.

By 1460 Sir Thomas was the Duke of Exeter’s right-hand man and after the Yorkist landings recruited men for the Lancastrian cause and led them to break the Yorkist siege of the Lancastrian held Tower of London. However, this triumph was short lived as on 10th July the king’s supporters were defeated at the Battle of Northampton, mainly due to the treachery of some of the king’s supposed supporters, and savage retribution was soon inflicted on some of the defeated Lancastrian supporters.

Browne was convicted of treason and sentenced to death on 20th July, but reports of when and how he was executed are at variance. One report has him being immediately executed by beheading, whilst another has him and five others executed by hanging, drawing and quartering on the Tyburn gallows on 29th July.

The Browne family fortunes were restored after the Battle of Tewksbury when Lancastrian supporter George Browne, son of Sir Thomas, achieved Royal favour and was knighted and also had his father’s estates restored to him, these included Hartanger and the Barfreston mill. The family adherence to the Lancastrian cause once more brought about the downfall of their fortune when in 1483 Sir George Browne joined in the Kentish Rebellion against the recently enthroned Yorkist King Richard III. After the defeat of the rebellion Sir George was imprisoned and then executed for treason and in January of 1484 his estates were declared forfeit to the Crown by Act of Attainder. In August of that year King Richard III rewarded Sir William Malyverer for services against the rebels with the ward of confiscated property which included “Hertang (Hartanger), and Paratt’s landis [Perot’s Land?], (both) in the parish of Berston (Barfreston); also a windmill called Berston Mylle; (Barfreston mill)”.

Malyverer was also made Escheator for Kent, a potentially lucrative Royal appointment. An escheator was responsible for escheats, the reversion of lands in English feudal law to the lord of the fee when there are no heirs capable of inheriting under the original grant.

William Langley of Knolton and Hartanger had died in February of 1483, leaving his son John, a minor, as his heir. Joan, William’s newly widowed wife, appears to have married William Malyverer shortly after William Langley’s death, possibly for political reasons, but most likely under duress.

Church Farm House in Barfreston. Parts of the house date back to the late 15th century or possibly earlier. The 18th century brickwork facade hides the original timber framed construction.

In November of 1483 Malyverer seized the Kent lands of his newly acquired wife’s late husband which had previously been granted along with the wardship of the young John Langley to Richard Guildford (Guldeford) of Rolvenden, Kent. As one of the leaders of the recently failed Kent rebellion Guildford had subsequently had his estates confiscated by the Crown. Such was Malyverer’s power in this time of ineffectual central authority that despite a Royal grant awarding “the warde & marriage of John Langley son & heire of the said William; with the keeping of alle Lordshipds ect” to Joan Langley and Thomas Quadring he managed to retain possession of of his step-son’s property, probably by use of his office as an escheator, until August of 1485 when Malyverer’s power and authority in Kent came to an abrupt end when his patron Richard III was defeated and slain at the Battle of Bosworth and Henry Tudor became King Henry VII.

After the downfall of Malyverer the land and property confiscated from Sir George Browne were restored to his heirs and the remained with the family until around 1566 when Sir Thomas Browne sold his land and property at Hartanger to Mr. Thomas Boys, a son of William Boys of Fredville, then then living at adjacent Elmington, now Elvington.

Thomas Boys died in 1599, and his eldest son, Thomas Boys of Hoad, inherited Hartanger, which in turned passed to his eldest son and heir, John Boys of Hoad, who sold Hartanger at the latter part of the reign of King Charles to Anthony Percival of Dover, who was comptroller of the customs at Dover.

Around 1646 the Percival heirs sold Hartanger to Major Richard Harvey whose family lived there for several generations until Richard Harvey sold the estate to John Plumptre of Fredville in 1792.

Richard Harvey was the father of Captain John Harvey who had commanded H.M.S. Brunswick against the French fleet at the Battle of the Glorious First of June in 1794. John Harvey joined the Navy at the age of 15 and in 1794, at the beginning of the French Revolutionary War, 1793-1802, was captain of the ‘Brunswick’, 74 guns. The was part of Lord Howe’s fleet in the campaign leading up to the Battle of the Glorious First of June in which the Brunswick was directly astern of Howe’s flagship, ‘Queen Charlotte’. Captain Harvey was mortally wounded in the action and died shortly afterwards and was later buried in Eastry Church and a memorial to his memory erected in Westminster Abbey.

Hartanger, now for the main part consisting of Church Farm in Barfreston, is still part of the Fredville estate. Most of the cottages that were part of the original 19th century Hartanger purchase have now been sold off.