In its extreme northern corner the old parish of Nonington was bounded by the parish of Goodnestone to the west and to the east by the parish of Chillenden, which was absorbed into the parish of Goodnestone in 1935.

This corner is still a part of the present parish of Nonington and here, in the shave adjacent to the ancient trackway known for the last four hundred or more years as Cherry Garden Lane, is to be found a mound of earth or tumulus known as Mount Ephraim. Cherry Garden Lane derives its name from the cherry gardens or orchards which occupied the land on the south western side of the trackway up towards the old St. Alban’s Court house from at least the early 17th century.

Above left: Mt Ephraim Mound as seen from Cherry Garden Lane-looking south.

Above right: Mt Ephraim Mound as seen from Cherry Garden Lane-looking west

Why the mound was named Mount Ephraim is lost in time, but it is a comparatively recent appellation as the name only begins to appear in St. Alban’s Court estate and other documents and maps in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. Possibly it derives from Moneketon or Mounton, the old name for what is known known as Gooseberry Hall.

The origins of the mound are not certain. In 1964 the Ordnance Survey Archaeology Division inspected the site and identified the mound as being that of a post-medieval windmill mound, but there is no documentary evidence in St. Alban’s Court estate or other sources regarding a windmill on this site.

Another possibility is that it is that it is an ancient round barrow, but without an archaeological examination this cannot be confirmed. The recent “Field report on Mount Ephraim mound off Cherry Garden Lane, Nonington: December 23, 2023” by Keith Parfitt of the Dover Archaeological Group notes:- “The close proximity of the mound to a junction of historic parish boundaries could be taken to indicate that it already existed as a convenient reference point in the local landscape when these boundary lines were first laid out, probably during the middle Anglo-Saxon period. The incorporation of prehistoric round barrows into subsequent land boundaries is widely known in the English countryside”.

The above field report records that “Inspection on the ground indicated that the mound was roughly circular in plan although trees and undergrowth made accurate observation difficult. There was no trace of any contemporary enclosing ditch. As measured in 2023, the mound was about 25m (NW–SE) by 27m (NE–SW). It stood to a height of between 0.70m (west side) and 2.00m (north side)”.

As to the construction of the mound Keith Parfitt writesthat:-“Observation of occasional animal burrows, together with the sides of a sunken pathway cut into its southern edge indicated that the upper part of the mound was composed of the local brown clay. There was no indication of any chalk being present”.

When first constructed the mound would most likely have been somewhat higher than at present and have been a prominent feature in the countryside before the present shave grew up around it. Keith Parfitt records in his report that:-“The mound shows evidence for a certain amount of damage. On the top of the mound a shallow, oval depression about 8–10 metres across appears to be of some antiquity but whether it is an original feature is uncertain”.

Literally a few yards to the north west of the mound is the site of an extensive early Roman military settlement immediately adjacent to Cherry Garden Lane which has been known about for some two decades or so but has yet to be excavated. If the mound pre-dated the Roman invasion and occupation of East Kent it is not beyond the realms of possibility that it was used for military purposes such as for the base for a watchtower or warning beacon. There is a clear line of site from the mound to down to the believed 43 CE Roman invasion landing site at Richborough [Rutupiæ].

There is some documentary evidence that the mound was there in the late 13th and early 14th centuries. In the late 13th century a John atte Berghe was a witness to a document concerning the sale of land in Moneketon, the present Gooseberry Hall area, which is a quarter of a mile or so down the hill to the east of Mount Ephraim. At this time family names were not often hereditary and to distinguish individuals with the same first name a physical characteristic, trade, or where they lived was used to differentiate them. John was a very common name in England at this time, it’s thought that over one third of adult males had this first name.

The suffix “atte Berghe or Bergh” would have been used to describe someone who lived on or by a hill, mound or barrow, and in this case I believe the “berghe” referred to is what was later to become known as Mount Ephraim.

Some years later in 1315 there is a record of a land grant by someone who appears to have been a descendant of the aforementioned John atte Berghe. The record is of an “Enrolment of grant by Walter son of Thomas atte Bergh of Eswele, in the county of Kent, to Sir Henry Beaufuiz, knight, of a messuage and 25 acres of land in Eswele”, Eswele later became a part of what was to be known from the late 15th century onwards as St. Alban’s Court.

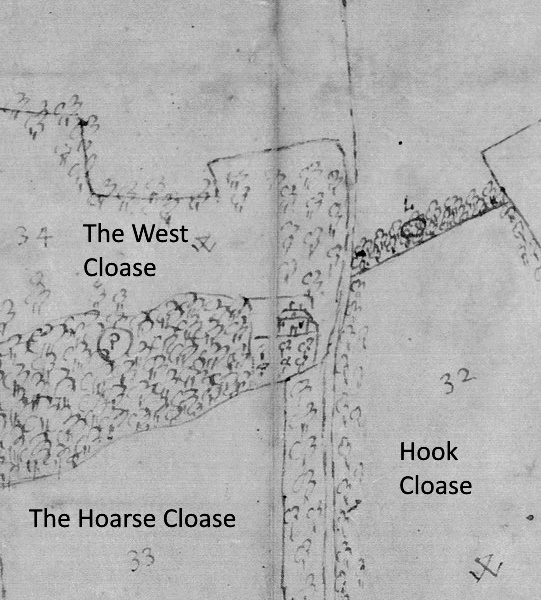

A few yards down the hill from the mound are the remains of what is most likely a late medieval brick building that stood on the site of Sir Henry’s messuage. This once high status building was demolished in the 1890’s and only a pile of bricks now remain to mark the spot. The earliest known reference to the old Mount Ephraim house is on a 1620’s map of the St. Alban’s estate. A sketch of the house is shown, but not the tumulus which is hidden in the wooded area just to the north west of the house.

Above left: an extract from a 1620’s St. Alban’s Court estate map of the area around Mt Ephraim.

Above right: a close up of the area around the clearly visible old Mount Ephraim house from the same map.

A year later the aforementioned and very well connected in Royal circles Sir Henry Beaufuiz applied for a Royal licence to enclose a lane between two of his gardens, meaning orchards, and the licence was granted on the provision that Sir Henry made a new lane to the south of his gardens. Gardens at this time could also mean orchards or other small areas of enclosed land. This provision would apply if the lane to be diverted was a public Kings way or highway, which in this case appears to be what was later to be known as Cherry Garden Lane. Prior to the name Cherry Garden Lane coming widely used this ancient trackway that became a medieval King’s Highway of some importance was sometimes referred to in late 15th and early 16th century documents as St. Margaret’s Street as it can be followed in a westerly direction to Langdon and on to the present St. Margaret’s Bay. It is now thought that St. Margaret’s Bay was a small sea port until the 17th century when coastal erosion destroyed the protective southerly headland of the bay.

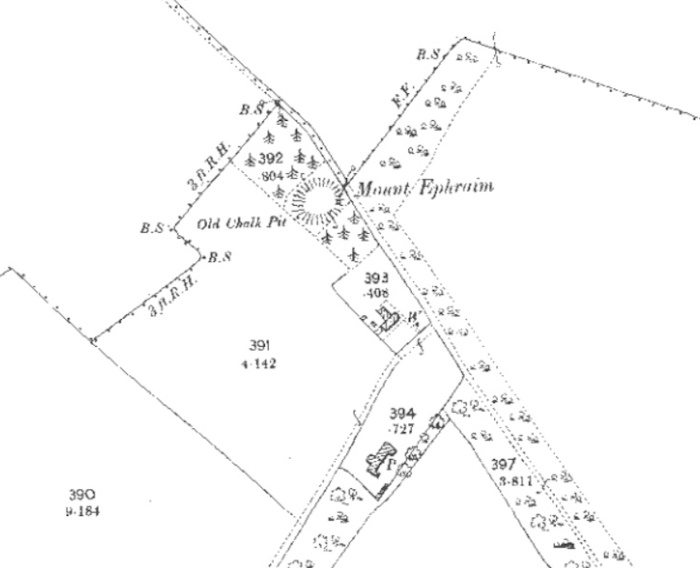

The Mount Ephraim area from the 1871 OS map. As can be seen, field boundaries have not changed in the 250 years since the completion of the 1620’s estate map.

Just below the remains of the old Mount Ephraim house on the south western side of Cherry Garden Way is a section of disused ancient sunken road which has the appearance of a wide ditch which in places approaching two or more metres deep. This is, I believe, the section of lane that Sir Henry closed and moved a few yards to the north east to form the present section of Cherry Garden Way.

This section of sunken road runs directly to the site of the old house and may therefore have originally run close to Sir Henry’s earlier messuage and was perceived by him to infringe on his privacy and security thereby compelling him to apply to have the lane diverted.

Above left: the entrance to the disused section of hollow way.

Above right: a section of the disused hollow way

The present Mount Ephraim house has a plaque with the initials W.O.H, for William Oxenden Hammond, the owner of the St. Alban’s Court estate, and the date 1867, presumably the year of construction. This double cottage was built to the design of noted country house architect George Devey as housing for St. Alban’s estate workers but was not shown on the 1871 OS map. During the 1870’s Devey designed and built the new St. Alban’s Court mansion and several other cottages for estate workers.

The Mount Ephraim area taken from the 1877 OS map. Both the old and new houses are shown, but the due to a cartographer’s error the tumulus is incorrectly labelled as a chalk pit.

++++++++++++