The village of Aylesham now covers most of Curleswood or Curlswood Park. Once an old deer park belonging to the Archbishop of Canterbury, it later constituted a large part of the six hundred acres of farmland acquired in 1924 from Henry FitzWalter Plumptre of Goodnestone by Pearson & Dorman Long for the building of houses for miners then working at the nearby Snowdown Colliery and a proposed new mine at Adisham, which was never developed.

The name Curlswood, or Curleswood, evolved over the centuries from its Anglo-Saxon name: ‘Crudes silva’, meaning Cruda’s Wood, with Cruda appearing in possessive form as Crudes in placenames. The earliest known reference to ‘Crudes Wood’ is in a charter of 873 in which King Alfred of Wessex, better known as King Alfred the Great, and Ethelred, Archbishop of Canterbury, granted land at Gilding [evolved to Ilding and is now called Ilden], to Liaba, the son of Birgwine, in return for a payment of 20 mancuses of gold. A mancus was a gold coin and unit of account with an equivalent value to 30 silver pennies.

In the charter the piece of land at Gilding is described as being bordered by land held by Sevres, a monk from Christ Church in Canterbury, to the south and west; by land at Bosingtune, now Bossington, to the north; and by Crudes silva, or Crude’s Wood, to the east.

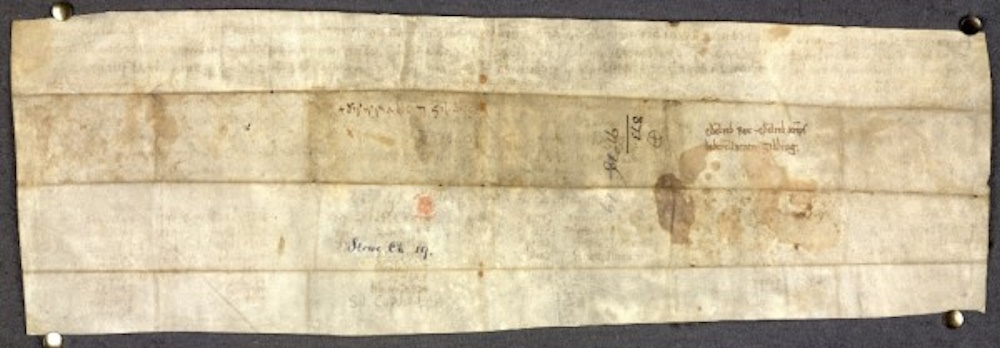

Grant of King Alfred of the King Alfred of Wessex & and Archbishop Æthelred of Canterbury to Liaba, son of Birgwine in 873 [S344]. Soon after it was made, a different hand added in English, ‘Leafa [another spelling of Liaba?] bought this charter and this land from Archbishop Æthelred and from the community at Christ Church, with the freedom as that given to Christ Church, in perpetual possession’.

On the back [dorse] of the document, a contemporary scribe wrote, ‘This is the charter for Gilding’ [Ilden], so that it could be easily identified.

The origin of the name Crudes or Crude’s is not clear, but the English Placename Society believe that Crudes Wood most likely takes it name from a person called Cruda, a rare and now now lost Anglo-Saxon personal name which possibly derived from Old English or Germanic roots relating to being thick, fat, or strong.

This reference to Crudes Wood in a charter of 873 proves beyond reasonable doubt that the land on which Aylesham stands, and continues to expand over, was woodland some twelve hundred years ago at the time of King Alfred and was therefore almost certainly woodland when the Romans arrived in Britain eight hundred or more years before King Alfred’s reign.

Barratt Homes and Persimmon Homes, the present developers of “Aylesham Garden Village” have employed a team from the Faversham-based Swale and Thames Archaeology (SWAT) to undertake an ongoing archaeological investigation in advance of the building of houses as part of the “Aylesham Garden Village” development. The SWAT investigations of the land that was once Crudes Wood have revealed Anglo-Saxon burials, evidence of Roman military occupation and pottery making, and pre-Roman artifacts.

In a widely reported general press release by SWAT in 2020 Dr. Paul Wilkinson said:

“It will be some time before we know much more about the skeletons and their graves. However, the other items we have found have helped to fill in some big gaps in our knowledge of post-invasion Roman life.

“We are quite certain we have discovered what was a military supply depot on the Aylesham site. This would have been set up a year or two after the Romans invaded Britain and we believe would have been manned by soldiers of a Roman legion.

“Not all of them would have been fighting men but specialists in a range of support roles – similar to the British Army of the Victorian era – and would have been posted around an area to concentrate on infrastructure tasks.

“At the center of the Aylesham site were three kilns for firing pottery which was bordered by trenches and ditches.

Local clay would have been used to make the army’s pots, plates, and urns. We have found glass items from Gaul, now France, and other pottery from Germany in Aylesham as well.

“We have discovered some of the urns found in Aylesham were made in the Medway area and these, with local-made items found, suggest the Romans were mass-producing everyday items quickly and efficiently.

“The site sits on the high ground offering sweeping views of the countryside in a triangle with Canterbury and the Roman ports of Richborough and Dover. It isn’t far from the strategically important Roman Watling Street connecting Dover and Richborough to Canterbury and beyond to Roman London.”

Since this 2020 press release little has been generally released of any further archaeological discoveries.

At the time of the Roman occupation of the site Crudes Wood would have provided wood to make the charcoal needed to fuel the pottery kilns and timber for the construction of the military buildings and associated structures.

In his press release Dr. Wilkinson refers to the site’s location on high ground and its “offering sweeping views of the countryside in a triangle with Canterbury and the Roman ports of Richborough and Dover”. This elevation was put to good use in later years for the defence of England against such threats as the Spanish Armada and the post-Revolutionary French under Napoleon Bonaparte.

At the Womenswold turning off of the B2046 road to Wingham is a modern reproduction of a warning beacon which was part of a chain of built in the 16th century, probably replacing earlier ones, to give warning of invasion.

A few hundred yards along the B2046 to Wingham a building know as Telegraph Cottage used to stand in the field on the eastern side of the road just before the Spinney Lane and Well Lane turning.

Telegraph Cottage was originally part of a chain of ten shutter telegraph stations traversing Kent from the Admiralty telegraph in Southwark to the naval yard at Deal which opened in 1796 to allowed rapid communication between London and the naval anchorage in the Downs off of Deal. It was said that a message could be transmitted from London to Deal in less than fifteen minutes. The next station in the chain of stations in the direction of Deal was at the present Telegraph Farm at Tilmanstone. Telegraph Cottage belonged to the Admiralty until the mid eighteen hundreds when it was sold off after the widespread introduction of the electric telegraph. Sadly, the cottage was demolished in the 1970’s.

Over the centuries the name Crudes Wood evolved and variations of the original name were used in medieval and later documents and maps: Crudeswod; Curlswood; Curleswood Park: Turleswood Park: Crowds Wood Park, Charles Wood Park and Curleswood Park being but a few. Some maps dating from the early 19th century even refer to it as Nonington Park, but later in the 19th and early 20th centuries it was generally referred to as Park Farm, with the Park suffix as a reminder of its use as a deer hunting park by the medieval Archbishops of Canterbury.

Curlswood Park, later Old Park Farm: from the 1877 OS map.

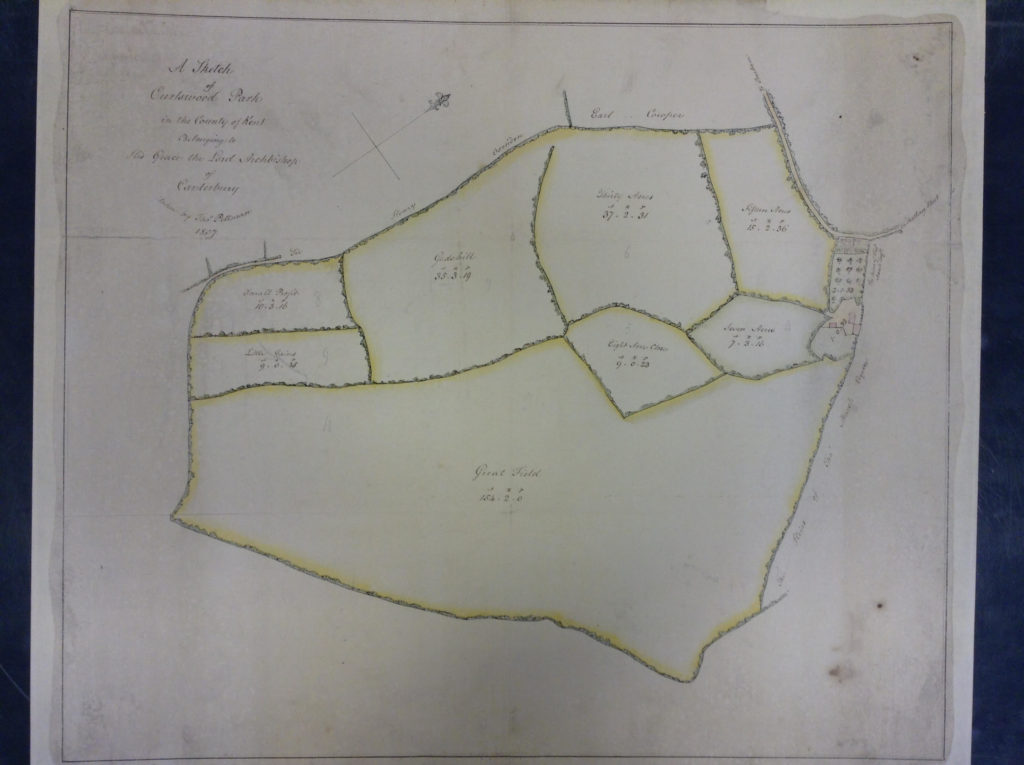

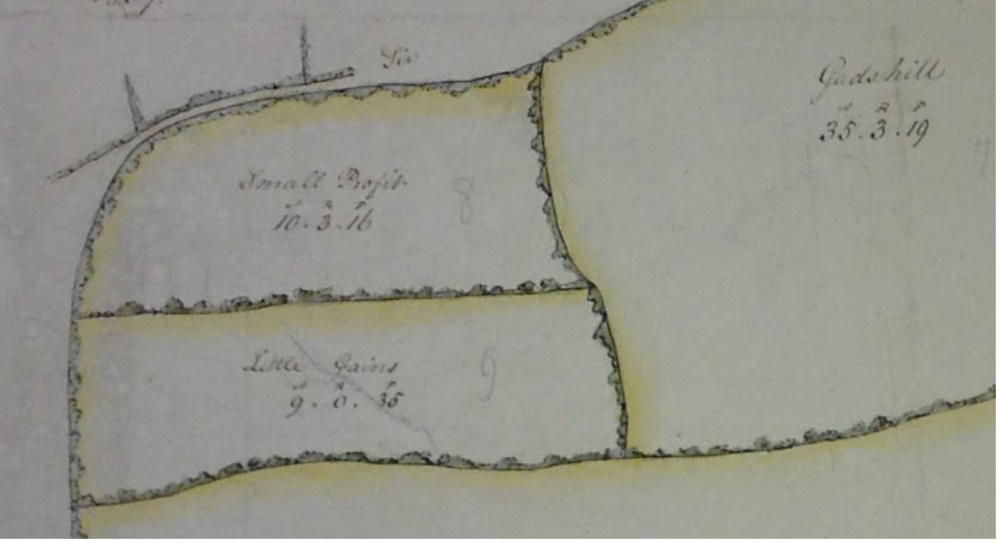

Curlswood Park had a boundary with the hamlet or vill’ of Ratling and may have been included in the vill’ in pre-Norman times. Ratling is said to derive its name from the Old English (O.E.). ryt hlinc; literally a rubbish slope, an area of little use for agriculture. Further evidence of the poor nature of the land within the park can be found on an 1807 map made by Thomas Pettman for the Charles Manners-Sutton, Archbishop of Canterbury., see below, which records the field enclosure names at the southern end of the park as “Small Profit” and “Little Gains”. These same names are recorded on the 1839 Nonington tithe and the 1859 Nonington Poor Law Commissioners maps. “Small Profit” and “Little Gains” are now covered for the large part by the Aylesham industrial estate between Spinney Lane and the B2046 Wingham Road.

Curlswood Park. An 1807 sketch map made by Thomas Pettman on behalf of Charles Manners-Sutton, Archbishop of Canterbury.

Curlswood Park, house and gardens in 1807. Ratling Street is in the top right.The road going to the left is the present footpath out to the B2046 Wingham Road and on the Adisham.The hedge on the left of the footpath as you walk towards the Wingham Road is one of the remnants of the deer leap that once enclosed the park.The eastern [right hand] boundary is now the Ratling Road from Aylesham.

Small Profit and Little Gain, now partly under the Aylsham industrial estate with the overgrown remainder now forming Spinney Wood. The road along the western [top] boundary is the B2046 Wingham Road.

The Kilwardby Survey of 1273-74 contains the manorial accounts for most of the Archbishop Kilwardby of Canterbury’s demesne manors in South-East England; a demesne was a holding directly under the control of the lord of the manor providing him with both food and income. The following extracts refer in part to Crudeswood (Curlswood) as a demesne of the Manor of Wingham:

Amercements, farms, and pannage:-

An amercement was a money fine levied in the manor or hundred court for a misdemeanour and pannage was a tax paid for the right to graze pigs in woodland.

Swineherds beating down acorns for their pigs:from the Queen Mary Psalter, written between 1310 and 1320.

“And of 25s from John Dene, the reeve, for a false presentment upon the account and of 12s for the farm of a curtilage and of 9s for the farm of the same in the previous year and of 18s for pannage in the Weald, the tithe having been deducted and of 24s for pannage in Crudswood, the tithe having been deducted and of 18s for the pannage of Wlveche, the tithe having been deducted and of £11 13s 4d from wood at Sandhurst sold.

Wood, item underwood sold.

And of 59s 6d for 18 [acres -omitted] of underwood in Wlveche [Woolege] sold and of 10s for 3 acres of underwood at Crudswood and of 34s for 8 acres, half a perch of underwood sold there“.

~~~

The cutting and sale of the underwood, such as hazel and ash, appears to have been quite lucrative. The woodland would have been harvested [coppiced] on a regular rotational basis and sold for use in fencing, wattling for building, and for fuel. Pigs would have been grazed in the woodland during the autumn when they would have fed on acorns and other autumnal fruits and fungae.

Oak trees would have been allowed to grow to maturity for use in the building of houses and possibly ships, and as they grew to maturity the oak trees would have had their larger lower branches harvested for use when smaller pieces of oak were needed. Elm and lime were other important species of trees with a variety of domestic and other uses that would have been allowed to grow to maturity.

In 1282 Nonington became one of the four separate parishes making up the College of Wingham and between 1283 and 1285 Archbishop Pecham commissioned a survey of his possessions. Cruddes Wood, as Curlswood Park was then known, was part of the Cotland of the College. Cotland was an inferior type of land tenure, usually in woodland, with some rights such as grazing attached.

There are two large woodland belonging to the manor of Wingham in or nearby to Nonington. Cruddeswode which the survey records as covering 244 acres, and another at Wolnuth (Woolege Woods near Woolege Green) recorded as 296 ½ acres in extent. There was another large wooded area at Oxenden, the present Oxney, which covered some fifty acres or so.

The Pecham survey records two tenants at Cruddeswode, Richard Hokemok, who held two parts, and Rikemund, the widow of Alexander Crud, held the third part. Curlswood was bordered to the east by Wingham manor’s vill’ of North Nonington and by its vill’ of Ackholt to the south-east.

At some time during the late 13th or early 14th century the cotland at Cruddeswode was was enclosed and brought into use as a deer park.

To establish a deer park a Royal licence was required, known as “a licence to empark”. The purpose of a deer park was to keep deer, usually Fallow or Red deer, for the land-owner, usually the lord of the manor, to hunt for sport and to use as a source of fresh meat during the winter. The deer park was generally an area of mainly woodland that was usually totally enclosed by banks with an inner ditch with the bank having either a pale or thorn hedge, or sometimes sections of each, on top of it. These banks were known as deer leaps and they were designed to stop deer from escaping from the enclosed deer park and to prevent two and four legged predators and foraging livestock from entering.

The pale was a fence made by driving stakes close together into the ground to form a barrier and some substantial lengths of the original deer leap bank enclosing Cruddeswode survive and are, at least at present, still clearly visible along the original deer park’s north-eastern boundary with adjoing Ratling Court’s land, now marked by a bridleway, and along its boundary with the B2046 Wingham road.

It would have taken a lot of money, labour and time to enclose and establish a deer park and a lot more expense to maintain it. A hunting lodge was usually built within or nearby to the parks boundaries, in the case of Cruddeswode this was most likely built on the site of what later became Curleswood Park farm house and farm yard. The deer park would have been for the use and entertainment of the Archbishop and his friends but in July of 1360 two Royal visitors enjoyed a days hunting there.

~~~~~~

The Black Prince & King John II of France visit Cruddeswode.

During the Battle of Poitiers in 1356 King John II of France, known as John the Good, had been taken prisoner and subsequently held to ransom for the sum of three million crowns, roughly two to three times the gross revenues of the kingdom of France. The French king enjoyed a very comfortable imprisonment at various places in England, his account books for his time in captivity record that he had a personal retinue, or court, that included an astrologer and a court band and that he spent large amounts on horses, pets, and clothes.

King John remained captive until the drafting of the Treaty of Brétigny in May of 1360, which set out the terms of his release and led to the king leaving his final place of imprisonment in the Tower of London on 30th June, although the treaty was not actually ratified until October of that year. At the time of the French king’s imprisonment at the Tower of London the Constable of the Tower was Sir John de Beauchamp, who fought alongside Edward of Woodstock, the son and heir of King Edward II and better known to history as the Black Prince, at Poitiers and several other battles, and had a manor house a mile or so to the east of Cruddeswode at Esol, just off of Beauchamps Lane in what is now Easole Street in Nonington. As Constable of the Tower is very likely that Sir John would have been a member of the entourage escorting King John on his journey to Dover as in keeping with his royal status the French monarch would have expected to have high ranking officials in attendance on his journey.

John II the Good, King of France. 14th century French School. Louvre Museum, Paris.

From the Tower John II proceeded to the Palace of Eltham where Queen Philippa of England gave him “a great farewell entertainment”. After passing the night at Dartford, the newly freed king travelled on towards Dover en route for Calais, which was at that time held by the English. On 4th July he broke his journey to visit the Maison Dieu of St. Mary at Ospringe near Faversham and later to pray at the shrine of St Thomas Becket at Canterbury Cathedral and afterwards spent the night in Canterbury.

The funerary figure on the tomb of Edward of Woodstock, better known to history as the Black Prince, in Canterbury Cathedral.

Early on the morning of Sunday 5th July the King left Canterbury to continue his journey to Dover in the company of Prince Edward of Woodstock, the Prince of Wales who later became better known to history as Edward the Black Prince. It is not recorded whether the Prince had been in company with the King all the way from London, or whether he joined the entourage at Canterbury. On the way to Dover the royal party passed through the park at Cruddeswode which belonged to the Archbishop of Canterbury. On passing through the Chronicon Anonymi Cantuariensis, a contemporary narrative written at Canterbury that provides valuable insights into medieval war and diplomacy, records that the Royal party “had there a fine procession of wild beasts”, most likely fallow and roe deer especially bred and maintained for hunting.

Although it is not recorded it’s possible that Sir John de Beauchamp, who’s Esol manor house was only a mile or so to the east of Cruddeswode at Esol, may have been in the French king’s escort from London to Dover in his capacity as Constable of the Tower of London and therefore also participated in the hunt at Cruddeswode. In addition to being the Constable of the Tower of London Sir John was also the Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports and Warden of Dover Castle, so if he was not in the French monarch’s escort from the offset due to his not being in London, then he may have taken part in the hunt and subsequent entertainments in these capacities. Sir John would have been well aware of the Archbishop of Canterbury’s hunting park close by to Esol, and it could well have been him that suggested that the royal party paid a visit to hunt there. The hunting must have been thought to be of a very high quality if it was considered to be fit for a King and a Prince of Wales!

Pursing a stag on horseback with hounds. Fallow and red deer were the usual quarry, and hunting them was exclusively the preserve of royalty and the rich and powerful aristocracy. Strict laws governed who was allowed to hunt. When the quarry was brought to bay the chosen hunter would despatch it with a hunting spear or hunting sword.

After the hunt at Cruddeswode the Royal party continued on to Dover where the King appears to have spent the night “ in Domo Dei Dovorrae” or “the House of God in Dover”, which would have been the present Maison Dieu.

The following day, Monday 6th July, the Black Prince gave “a great feast of fish and meat” for the King of France at Dover Castle, possibly with Sir John de Beauchamp and other local notables in attendance.

At around nine o’clock in the morning the day after the feast the French king left Dover by ship for Caleys, as English occupied Calais was then spelled, on a journey that took some eight or nine hours. As a guarantee of payment the French monarch left his son Prince Louis of Anjou in Calais as a replacement hostage and he was then permitted to return to France to raise the agreed ransom.

After a breach of the terms of the Treaty of Brétigny caused by the escape of Prince Louis from Calais, the king voluntarily returned to imprisonment in England where he died in 1364. Only a third of King John II’s ransom was actually ever paid.

~~~~~~

In 1425 there was a grant of property at Akholte concerning Thomas Hunte, an official at Cruddyswood:“Akholte, June 21, 3 Hen. VI. (1425) John Helar, son of John Helar, late of Akholte in the par. of Nonynton, Kent, grants to Thomas Hunte parcarius* of Cruddyswood a croft** of 5 acres with appurtenances at Akholte between the common way of the vill of Akholte on N. and land of Thomas Hopedey on E. and Court land of Lordship of Akholte on S. and W. Warranty against all men. Witnesses: John Orlyston, John Marchaunt, Thomas Hopedey, John Cook, John Veryar’, Gervase Dudeman, Richard Guodhyewe. Thomas Lewar’, John Bery, Richard Beniamyn and others”

*A parker or park-keeper; a pinder; a foldkeeper. A pinder was an employee of a landowner who would go around and collect the rental dues from the tenants on the land. If the tennants could not pay in money, the pinder would take livestock in lieu of payment and put them in the pinfold until they could pay.

Also, the pinder would catch any livestock that had got loose and put them in the pinfold and would charge a price to the animals owner to get it back.

**A croft:- a small enclosed field or pasture near a house. A small farm, especially a tenant farm.

The croft referred to was possibly the present Keeper’s Cottage at Acol or another now demolished house that stood on the slope to the west of it.

Curlswood or Old Park Farm, from the 1859 Poor Law Commissioners Map of Nonington. Just to the north-west of the farm buildings is the remains of the deer leap which formed the boundary there with the land attached to the Canonry of Wingham, part of the College of Wingham founded by Archbishop Pecham in 1287.

Edward Oxenden de Dene, the eldest son of Thomas Oxenden de Dene, of Dene near Wingham, was appointed Warden of Cruddeswood [Curlswood] in 1501. A warden was usually a favoured appointee chosen by the park’s owner from a local land-owning family to be in overall charge of a deer park and to be in charge of the arrangements for deer hunts. Wardens usually had a deputy whom they paid to deal with the day to day administration and security of the park. The Oxenden family originated from Oxenden, or Oxney, another of the vills on the Archbishop’s manor of Wingham about a mile and a half to the south-east of Cruddeswood.

The College of Wingham was broken up during the reign of Henry VIII but the Curlswood deer park was retained by subsequent Archbishops of Canterbury and the land was leased out to a succession of lessees over the following centuries. The granting or leasing of land and property at favourable rates was frequently used by the Archbishop of Canterbury as a form of patronage. This appears to have happened with regard to Curlswood, which appears to have ceased to be a deer park in, or slightly before, 1586.

In 1586 Archbishop John Whitgift granted what appears to be the first lease for Curlswood Park, which then comprised of 180 acres of woodland and 60 acres of arable land, at a nominal rent of 20 shillings a year for twenty-one years to Miles Sandes, possibly a member of the Archbishop’s retinue who was the Member of Parliament for Queensborough on the Isle of Sheppey in that year.

Another recipient of this beneficial lease was Richard Massinger, who became lessee of Curleswood in 1595. He was a member of the Archbishop’s household and was elected Member of Parliament for Penryn in 1601. In 1604 “Charles Wood Parke House” was occupied by John Cox, presumably as sub-tenant.

A survey of the Archbishopric of Canterbury’s lands in 1617/18 recorded Curlswood as consisting of 60 acres of arable land and 180 acres of woodland with 1 acre of woodland grubbed up. Curlswood was noted to not be part of any manor and leased from Archbishop George Abbot by William Selby, with Pownall as under farmer or sub-tenant. The lessee was probably Sir William Selby, who had inherited Igtham Moat in 1611. The lease was on the same beneficial terms as contained in the previous two leases.

However, it appears that Archbishop and his tenant fell out because there is a record for 1617 in the Exchequer Bill Book registering a legal dispute between the Archbishop and William Selby regarding Curlswood. The nature of the dispute is at present unknown, but the outcome seems to have been that William Selby lost his lease as another lessee is recorded in that same year.

The second lessee during 1617 was Sir Robert Hatton, another member of the Archbishop Abbot’s entourage who was knighted in 1617. Possibly the lease was taken in connection with his newly acquired status. Sir Robert served as Member of Parliament for Sandwich in the early 1620’s.

Subsequent Archbishops of Canterbury continued to lease out Curlswood, but at present there is a long interval of almost a century and a half during which time to whom and on what terms is was leased out is unknown.

From around 1758 Edward ffinch, a trustee of the estate of a Mr. C. Fielding, took the land on a twenty- one year lease at a rent of £ 954. 8/-. However, after only five years or so the lease was surrendered and re-assigned in a document dated March 15th, 1763 for the same rent to Sir Brooke Bridges, bart., of Goodnestone.

The lease was for: “all that messuage or tenement called the lodge. And all that land and pasture enclosed by pale and hedge and sometimes therein is mentioned used as a park for deer commonly called Turlswood Park or otherwise Crowds Wood Park situated lying and being in the parish of Nunnington aforesaid in the county of Kent. Containing by estimation two hundred and eighty acres of arable and pastureland”.

It’s interesting to note that some two centuries after it had been “deparked” that reference is still made in the lease to “the lodge”, presumably used as the farmhouse, and also to the pale, or fence, and hedges enclosing the old deer park. This reference to both pale and hedge indicates that both types of barrier were used to enclose Curlswood.

To function as a deer park it would have been open woodland, to allow for the pursuit of the quarry on horseback, with large trees grown for use in building [oak?] and under-wood [hazel, ash, and other useful species] for other purposes, such as fencing, wattle and daubing, or fuel for the Archbishop.In 1617 a survey recorded 60 acres of arable land and 180 acres of woodland, while this lease states that the estate contains “by estimation two hundred and eighty acres of arable and pastureland”. It is therefore apparent that the park was predominantly woodland well into the 17th century, if not later.

The 1758 lease refers to it as arable and pasture. Pasture would be the first use after the woodland was cleared. A possible reason for clearance could have been the sale of timber to the navy followed by use as grazing land and then arable as agricultural practices became more advanced and agriculture more profitable. The difference in acreage from the 240 acres at the time of the 1280’s survey to 280 acres in 1763 would be accounted for in the variations in the size of an acre over the centuries until measurements were standardised in the United Kingdom in the nineteenth century. The actual total of acreage recorded on the 1807 map adds up to a fraction of an acre over 284 acres in total, including the house and gardens.

The Bridges family continued to lease Curlswood from the Archbishop until the later part of the nineteenth century when they purchased it outright. In later years Curlswood was known as Old Park Farm and various members of the Pepper family, tenants of the farm in the 19th century, are buried near the rear gate of Nonington church yard, have Park Farm on their headstones.

The village of Aylesham now covers most of the old deer park, which was part of the six hundred acres of farmland acquired in 1924 from Henry FitzWalter Plumptre of Goodnestone by Pearson & Dorman Long for the building of houses for miners working at the nearby Snowdown Colliery and a proposed new mine at Adisham which was never developed.

Sir Patrick Abercrombie, the renowned architect and town planner, was commissioned in the 1920’s to design the new mining village of Aylesham, and he derived inspiration from new towns such as Letchworth and Welwyn Garden City in Hertfordshire. The building of houses to accommodate the expanding labour force at Snowdown Colliery began in 1926.

Henry Fitzwalter Plumptre had inherited the Goodnestone estate in 1899 as heir to Sir George Talbot Bridges, the eighth and last Baronet. He was the grand-son of Henry Western Plumptre, a younger brother of John Pembleton Plumptre of Fredville, who had married Eleanor Bridges, the only daughter of Sir Brook William Bridges, fourth baronet, in 1828.

Old Park Farm after the the building of Aylesham had begun. Aylesham Holt railway station, just below Curlswood Park Farm, opened in 1928.

The last occupants of the Old Park Farm house and remaining buildings were the Hillier family who ran a fruit and vegetable business from there until after the Second World War. The house and farm buildings were eventually demolished in early 1950’s.