Miss Gladys Wright, founder and first principle of Nonington College & co-founder of the English Gymnastic Society (EGS)

A lady who had sudden and alarming acts of faith

or

How to found a college with no money!

By the late 1920s St Alban’s Court was being rented out to Commander Arthur O’Brien and his wife Marjorie. Carrying on the tradition of the Hammonds, the couple immediately took an active role in local life, attending and hosting many events, and sitting on various committees, on Armistice Days the Commander led the parade in the village to the war Memorial. The couple were noted for their love of horses and riding, and for breeding German Shepherds and other dogs for which they won lots of prizes at shows. Some of their dogs and horses were buried behind the house. Their country idyll was rudely interrupted when, on 30 March 1933, Marjorie returned to the house to discover jewellery worth about £500 had been stolen. A local newspaper report mentions that £1500 worth of jewellery had also been stolen from Chilham Castle, so perhaps a specialist thief or gang was operating in the area. By 15 February 1935 the O’Briens had left St Alban’s Court, and I assume St Alban’s Court lay empty as Mrs Ina Hammond considered what to do next.

Sturry, near Canterbury. Kent Archives.

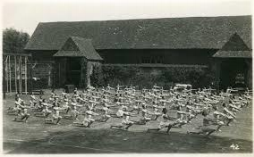

Meanwhile as Linda showed last week, Gladys Wright appears to have become something of a gymnastics and dance entrepreneur. In 1923 she had set up the English Scandinavian Summer School of Physical Education, and held annual vacations at Milner Court, Sturry. In the late 1920s Milner Court became part of the junior school of The King’s School Canterbury, but I assume the School was happy to continue renting out its facilities during vacations. The tithe barn at the school was converted into a modern gymnasium probably on Gladys’s initiative, but who funded this I cannot tell. A newspaper report of the annual school in August 1934 stated that women of ten nations took part in a display of gymnastics according to the Bjorksten method, this was followed by folk dancing, some in national costume, and the event concluded with diving. The newspaper reported that Gladys’s ethos was “It is not only a brain, not only a body we have to educate, but a whole human being.” The public displays at these summer schools attracted large audiences, and some were recorded on film.

Now Gladys and Stina Kreuger decided to take their ideas to a wider audience. On 5 May 1934 The Citizen newspaper reported that Gladys had sold every seat, nearly ten thousand, in the Royal Albert Hall for a display of “recreational gymnastics”. This was during a sell-out tour that had taken in Edinburgh, Glasgow, Leeds, Liverpool, Nottingham, Newcastle and Birmingham. Gladys and Stina had put together a team of 32 gymnasts composed of women students from Helsingfors, men from Stockholm YMCA, and British gymnastic teachers. Gladys and Stina booked the venues, organized travel and accommodation, and arranged the transport of 2 ½ tons of equipment, no mean feat. A Major General, who had been the senior British medical officer in WW1, spoke at one of their displays he was clearly impressed by what he had seen. Privately he had been concerned at the poor physical condition of British Army recruits he had seen during WW1, and thought something needed to be done about it before another war came along. In 1934 Gladys also founded the English Gymnastic Society to promote her ideas and to fundraise. At the time she was also probably working as a lecturer at Chelsea College, located close to her rented accommodation in Gunter Street, Chelsea. Gladys was running the tour and the annual schools presumably during her vacations, but clearly preparing for these was a round the year occupation, all this while holding down a lecturing post, no mean feat. Perhaps it was at this time that Gladys and Stina saw that they could make more effective use of their time and effort if they had a permanent base for their gymnastics.

Ancestry.co.uk.

Gladys’s pioneering work did not go unnoticed, in 1935 she was awarded the Golden Cross of the Order of the White Rose of Finland, by the president of the Republic of Finland in recognition of public service to the cause of gymnastics and Anglo-Finnish relations.

Meanwhile Ina Hammond had decided the time had come to sell the ancestral home and its large estate, spelling the end of a 500 year association between the Hammonds and Nonington. In the 16 July 1937 edition of The Dover Express and East Kent News there appeared an advertisement for a “BEAUTIFUL ELIZABETHAN STYLE RESIDENCE” which was “suitable for gentlemen’s occupation”. Further advertisements followed including a larger one with photo in Country Life where the price for St Alban’s Court was given as £8,000 to include 49 acres, a number of farms, cottages and a further 1000 acres were also available to purchase. Glady and Stina would have been at the summer school at Milner Court, Sturry when some of these advertisements were published, and it is perfectly feasible that they took a ride out to Nonington to look at the house and perhaps meet with Ina Hammond. By this time Gladys and the English Gymnastic Society had been fundraising since 1934 and had £300 in the bank. To establish a college at St Alban’s Court would require the £8,000 purchase price, plus £4,000 for a gymnasium, and further sums for the building conversion, beds, bedding, office equipment, staff recruitment and salaries, gymnastics equipment, books, and marketing, perhaps £20,000 in total. The English Gymnastic Society was £19,700 short of this target! It must therefore have come as a surprise to those in the know when, on 19 November 1937, The Dover Express and East Kent News reported “it has been possible with that sum in hand [£300], to sign the contract to buy St Albans Court.”

Archaeological Society newsletter number 94 Autumn 2012.

So far I have not identified where the remaining money came from, perhaps Gladys negotiated a lease arrangement with Ina Hammond, or more probably there were wealthy backers in the background. Of note is the fact that one of the College’s first teachers was Florence de Horne Bevington a physiotherapist who had run her practice from a desirable address in London. Florence was the daughter of a wealthy Lloyds underwriter who had died in 1929. Florence had inherited £20,000 in Great Western Railway shares alone (value in 1930), and on her death in the 1970s had considerable assets. I imagine that Florence and others were sufficiently impressed by Gladys and her plans to want to invest in them.

News 16 July 1937.

During the winter and spring of 1937-38 St Alban’s was rapidly converted from country pile to college with lecture rooms, offices, accommodation, a dining hall, and gymnasium (now a listed building). The gymnasium was designed by Miss Jocelyn F Adburgham L.R.I.B.A., A.M.T.P.I, and built by G.H. Dene and Son of Deal in just two months. The gymnasium was designed to last 60 years, and to be relatively maintenance free there being no painted surfaces to repaint, it was constructed out of a range of timber including Swedish red pine, western red cedar, and Tasmanian oak. The Dover Express and East Kent News reported that:

“The most interesting feature of the college is the new gymnasium, built to the rear of the house. Costing nearly £4000 to erect, it is claimed to be the largest all-timber building in England, equalled in size only by the famous theatre at Oberammergau.”

Versions of this short quote landed up in newspapers all over the UK including The Broughty Ferry Guide & Carnoustie Gazette! In the house the National Association of Teachers of Physical Education supported by the Hungarian government paid for a Hungarian room furnished in a peasant style. While Swedish and Danish rooms were also promised.

1938.

Finally on Saturday 23 July 1938 Nonington College of Physical Education was opened by the Archbishop of Canterbury Cosmo Gordon Lang, who gave a rousing if not controversial speech, he concluded with:

“With very good heart and high hope, I declare St Alban’s Court open, and I invite the guardian spirits of health and joy and comradeship to enter and progress it.”

There followed a speech by the secretary to the Finnish Legation who highlighted the close links between Gladys Wright and his country. Then Mr Barclay Baron (closely linked to the YMCA and Toc H) finished by highlighting the impressive work the team from Dene had done on the gymnasium, and then finished with:

“Miss Wright, the principal, was a lady who had sudden and alarming acts of faith. Taking St Alban’s had been one of these and it had been admirably justified. It was a great power house from which would go out a band of people whose powers would be exerted not only on the muscles but on the minds and spirits those whom they trained.”

The ceremony concluded with girls from Brentwood County School giving a gymnastic display. The local paper noted that the College could accommodate 60 students who would study for three-year diploma courses, with the first term starting on 29 September 1938. While the summer schools would also continue, with one already underway with 200 students taking a three-week course.

The College had now officially open, though its first intake of full-time diploma students had yet to arrive. By hook or by crook Gladys had achieved her aim of founding a centre for gymnastics.

In the next installment I will look at the challenges the College faced in its early days, how its students and staff fitted into local life, and then the turmoil of World War 2 which threatened to spell the end of Nonington College itself.

Stephen Burke

January 2021

Bibliography:

For this installment I relied heavily on the British newspaper archive on the Find my Past website.

Gill Clarke and Ida M. Webb. Gladys Frances Miriam Wright. (Oxford, 2007) available here by

subscription https://doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/93577.

www.nonington.org.uk This is a tremendous resource for Nonington and the College.

www.ancestry.co.uk

www.findmypast.co.uk