An edited version of this article by Peter Hobbs, the present owner of Old St. Alban’s Court, was previously published in 2017 in Archaeologia Cantiana Vol: 138-pages 291-299.

Since 1519, the Hammond family had lived at what appears to have always been known locally as St Albans, substantially adding to and changing the original fourteenth century hall house built for their tenants by the Abbey of St Albans in Hertfordshire, owners of the ancient Saxon estate since 1097.(1) William Oxenden Hammond – see Fig 1 – formerly a soldier and now a successful banker, in 1875 wrote in the diary called ‘MSS Family Histories’ that he had consulted his brothers and “…decided to rebuild a new mansion (see Fig 3), the old one . . (Fig 2) . . . having naturally fallen into a decayed state.”(2).

He had already commissioned a new stable block and associated buildings as well as estate cottages from his friend the architect George Devey,(3) and appears to have added a tower and a new bay to the South East side of the existing house,(4) but it clearly left him dissatisfied, because he then commissioned an entirely new Elizabethan style mansion on a rise to the North of the old house.(5) He had also been improving and ornamenting his newly inherited estate with substantial tree planting around the new site – during which he unearthed human remains and reburied them under a stone pyramid (6) – so what was more logical than to consider other ways of enhancing the attractiveness of his property?

To the South of the old manor house there was a substantial hole in the ground – the first reference so far to this is as a property marker in the 1501 Court Roll of the Abbot of St Albans,(7) and it is present on a 1629 Estate map.(8) Given the ample presence of brick earth as well as documented and recorded brick clamps in the immediate vicinity,(9) it seems reasonable to assume that it was probably extended in 1556, when the old house was partially rebuilt in brick – and perhaps even further extended when the house was substantially remodelled in 1666.(10) Situated next to the Home Farm, the cavity then seems to have been used as a tip for what could not be spread advantageously on the land, and considerable fragments of eighteenth and early nineteenth century domestic refuse were recovered in 2001.(11) It may even have been further enlarged in 1790 when the mansion was again remodelled and extended.(12) At that time, a large brick built soakaway was inserted at the bottom linked by a substantial brick lined conduit to the rain water drains around the manor house.

This large cavity lay beyond the old roadway leading to the rear of the manor, immediately in front of the new 1869 Stable Block designed by George Devey, and adjacent to the Tudor walled garden. This had been re-equipped as a parterre with paths and glass houses in 1790, and refurbished at least in part in 1869 (13) with the completion of the new Stable block, and lay at the back of the old manor house. Hammond had also commissioned a new entrance to this walled garden from Devey which is dated 1869, and the 1872 Ordnance Survey(14) shows linked walks. It was again logical for Hammond to look to continue the enhancement of his inheritance by utilising the excavation for further display and linking it to his walks amongst the rose beds of his Tudor walled garden.

Where would he go to seek ideas and find contractors to carry out this sort of garden improvement? Presumably, he would have talked to his architect and friend George Devey, who would have been aware of appropriate names of which probably the most notable since the 1840s would have been that of the family firm of James Pulham & Son, based in Broxbourne in Hertfordshire. Devey had executed a series of commissions for the Rothschilds from the early 1860s, (15) and would have been aware of Pulham’s work for Rothschild at Waddesdon Manor(16). In 1877, Devey was also building the (later celebrated) Eythrope Water Pavilion for Alice de Rothschild in a bend in the Thames when the lady was persuaded that water was inimical to her sleep, so no bedrooms were provided, and she slept each night at Waddesdon!(17)

Rock gardening had developed in the earlier part of the nineteenth century as a fusion of the concepts of ornamental design and scientific interest. Some designers preferred to work with natural rock but the Pulhams exploited their own technology to enable large scale construction at a cost which allowed much higher expenditure on plants. Pulhamite – a render for artificial rockwork and in the form of a stone coloured terracotta material used for precast garden or architectural ornamentation – was the source of their reputation.(18) Although Pulham seems to have had only a dozen or so commissions in Kent by the 1870s – Barham Court near Canterbury had work done on Dropping Wells and pools in 1870 (19) – but Hammond’s commission appears to have been for the more expensive and conventional banks of natural rock although the formation of a Dropping Well and two associated pools could be Pulhamite. James 2’s Plan of the garden at St Albans Court is shown in Fig 4.

In the 1877 Pulham Brochure,(20) the work was categorised under ”Ferneries, rocky banks, alpineries and conservatories.” The South West side of the excavation was a shallow slope with rocks amongst grass as far as can be seen from the photograph in the 1937 Sale Catalogue for the Estate 21 – Fig 5, with the picture showing it as it is today in Fig 6. Within this, areas were linked by steps and paths of stone slabs. There was a prominent Toad or Frog stone to the West with small round planting holes appropriately placed to add to the illusion and another overlooking one of the Dropping Wells – see Fig 7. The Pulham Business Records show the work being carried out for Hammond in 1877,(22) – a year before he was able to move into his new mansion – so this represented but one strand of a vast construction project.

According to local accounts, the rock came by train to Adisham – then the nearest station – and then by horse and cart to Nonington – a distance of about three miles.(23) The rock itself is Wealdon level sandstone, most probably from one of the quarries at Maidstone. Pulham drew on local sources, and this appears to have been the nearest with rail connections.(24) The water for the Dropping Well came via a two inch cast iron pipe from a reservoir in the then kitchen gardens to the South East, closer to the hamlet of Easole.(25) Puzzlingly, no evidence of any link or drain to the large brick 1790 soakaway was found, although the soakaway itself is shown on the 1872 ‘25 Miles to the Inch’ Ordnance Survey, so it must have been known about. Devey himself directed all the roof water of the 1869 Stables Buildings – not into the old soakaway but into a large new cistern he had designed for the Stable Yard. In one hundred years, presumably, the emphasis had changed from eliminating waste water to saving it, something to reflect on with the current obsessions with climate change.

It is assumed that it was also at this time that a rectangular area of some eighty yards by thirty yards was cleared between the North Westerly end of the excavation and an existing walk extending from the Walled Garden. Excavation in 2001 (26) showed a depth of approximately two feet of soil on top of about twelve inches of compressed peat below which was a bed of gravel. The original chalky alkaline soil had been removed and replaced – probably with acid soil, although now it is neutral. Into this had been planted rhododendron of which only the toughest specimens still survive.

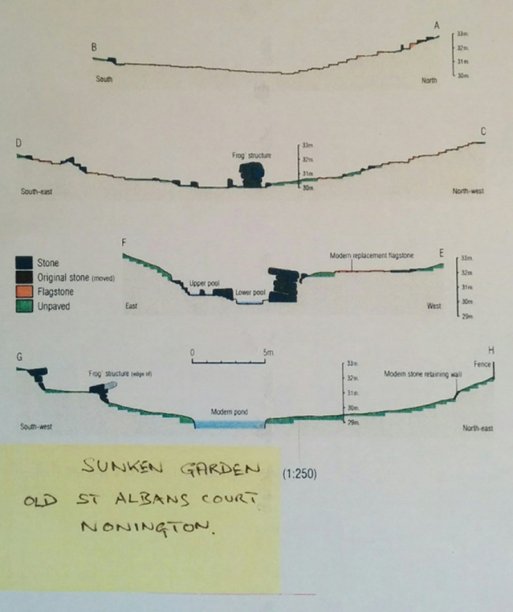

The immediate subsequent history of the garden is unclear. A tenant in the early 1900s may have extended the area of the garden – there are brick walls holding back banks of earth on the East side of the Dropping Well and forming a crescent containing another pool which could be later. However, the detailed survey carried out in 2013 (27) – Appendix 1 – showed up more brick crescents and banks on the West side. All were formed of the same machine brick, most probably from the Sittingbourne brickfields, and their siting in conjunction with and under rock makes the case for them to be part of the original construction. (28)

The 1937 Sale Catalogue states that the Margate Water Company had by then provided a tap at the end of a three-inch water main which is also remembered as providing two stand pipes on the slope to the South West. However, this was not connected to the Dropping Well.

Mrs Ina Hammond lavished care and attention on what the youngest of her grandchildren knew as ‘Grannie’s Garden’ where frogs abounded in the 1920s. They still do but her elder sister recollects only being chased off the rocks by Sayer the Gardener. (29) There are some grainy photos of small conifer planting in sites where there are now large trees and there are local recollections of children opening the sluice in the old kitchen gardens and running along the road to watch the water surge out of the Dropping Well in the sunken garden. (30). The 1937 Sales catalogue describes the area as “Large Sunk Garden with wide grass slope in centre and dripping well sheltered by large beech and chestnut trees …”and is accompanied by the photograph shown in Fig 5.

The next pictures date post war, after Mrs Hammond had sold that part of the estate to the English Gymnastics Society, and female students of what became Nonington College of Physical Education are shown in Fig 8 engaged in rituals of dramatic performance under the “frog” stone.

Some former students remember only sunbathing there! However, others remember classes being taken down there and student artists drawing plants as exercises. (31) The Head Groundsman recollects the difficulties in getting a mower down to the bottom when he was expected to mow it every week, and, in high summer, he was wary of the numbers of adders enjoying the warm rocks. (32)

Then came a major intervention: in 1951, Miss Wright and Miss Kreuger – the co-owners of the College – sold it to Kent County Council. Miss Wright – who had been Principal since the College started in 1937 – moved into a substantial newly built house (called St Albans) off Mill Lane in Nonington which overlooked her former demesne. She took with her not only a four-roomed Finnish Sauna (which she said had been a personal gift from a Finnish admirer, (33) but also transported and created there a large rockery from the stone imported by Hammond and used by Pulham to shape the long slope out of the garden to the South – Figs 10 and 11.

Ian Sayer suspects that more rock was also taken from the North Easterly side of the garden flanking the track to the rear of the Stables. A crude estimate (34) is that the new rockery absorbed between 10 – 15% of all the original imports. The area she cleared was filled by a large herbaceous bed surrounded by lavender, according to Ian Sayer. The extensive vegetation then in the garden shows up in a photograph taken before 1971,35 which shows a musical event taking place – see Fig 9. There is an orchestra of about twenty and a young audience of at least one hundred and fifty, which gives a good sense of the versatility and capacity of the garden at that time.

In 1972, Kent County Council began the work to expand the College with a large-scale building programme (36) which included a large block of student flats, as well as a restaurant off a new roadway, extending the ancient track leading to the rear of the old manor house. In the area largely cleared of Pulham stonework by the depredations of Miss Wright, the College built four staff bungalows which were to the South and South West of the sunken garden, but sufficiently close to require making a platform for the foundations, thus forming a cliff-like South and South West side, and cutting off old vistas. This radically changed the garden by closing it in, and the steady spread of the yew and conifer trees began to cut down the light and started to drive out the grass sward. However, children from the bungalows played amongst the rocks, and both staff and students used the area for barbeques.

The College closed in 1986 and maintenance was reduced to zero leaving only a multitude of rabbits trimming the grass. Sometime before, ploughing had cut the old Dropping Well pipe in the adjoining field, and the Great Storm of 1987 uprooted numerous trees, one of which fractured the water main which was then cut off. The closure of the College meant the abandonment of the space to nature and invasive Knotweed, and nothing happened until the arrival of developers in 1990 who replaced the pathways to the bungalows with roadways, dumping the spoil on the rhododendron bed – by then itself an overgrown, almost impenetrable mass of self-seeded and gale-felled trees and brambles.

Groves of Japanese Knotweed flourished – possibly a legacy of the Victorian planting – as well as swathes of bracken. At some stage during the College tenure, the name had been changed from the ‘Sunken Garden’ to ‘The Dell’. This name was perpetuated by the developers who had taken over the College, but its form and purpose were lost and forgotten, and became a matter of indifference other than as a potential hazard to its owners. A further problem was that the developers’ work in transforming the old student accommodation into some forty modern flats meant heavy construction traffic up the trackway from the main road and onto the site, which resulted in the roadway itself starting to subside into the sunken garden.

In 2000, the usefulness to the developers of the old bungalows and the sunken garden as a tax haven expired, and, due to a fortuitous incidental comment in a telephone conversation, the present owners were able to step in before it came on the open market. The first task was to erect a wall of stone-filled caissons along the length of the sunken garden flanking the roadway to prevent further collapse. This steepened the North West side of the garden and eliminated the path opposite the entrance to the Stable Yard down which Ian Sayer had brought his mower in College days.

The first inkling of what we had really bought came only in 2008, when the postman delivered a letter addressed to Mrs Hammond at St Albans Court – the postman said that it could only be for us! – from English Heritage concerning Pulham and the data base they were building of their work. By then, the area has been opened up, cleared and made safe, in so doing revealing the mixture of rubble and brick used to underpin the rocks. Rain and animal activity had largely emptied the obscuring mixture of peat and soil which had provided planting pockets.

A rectangular concrete pit was unearthed close to the Dropping Well, but the materials look different from those used in the other constructions and, when found, was still functioning as a marsh garden. The last College Head Groundsman remembered it as always being a fixture there which makes the construction well before 1956 when he began to work there officially. He recollected a further pool on the other side of the Dropping Well which had been abandoned when the rock that dammed the water had collapsed down the slope below, and this site was recovered under some feet of earth and stone which had washed down from above in the intervening years. No water source was detected during the excavations. Paths and steps were mostly in situ although slipped and eroded in some places by tree roots, rabbit activity and weather, but the plan of the nineteenth century construction remained clear.

The planting which initially would have been Victorian (37) was surveyed by Mr and Mrs Richard Hoskins, and the detail is contained in Appendix 2. Some of the original planting remains, but essentially we have the legacy of relatively intensive cultivation in the 1920s, followed by more institutional work by the College. The Japanese Knotweed has (hopefully) been exterminated by a sustained program of digging, burning and poisoning, and the bracken has been tackled similarly. The Dropping Well has been linked to a permanent water supply from a cistern installed by the College in the 1950s to service the Caretaker’s cottage. The water from the Dropping Well flows to a small pond, and from there by gravity into the 1790 sump now converted to a large cistern from which it is pumped into Devey’s cistern in the Stable Yard for garden use. The rediscovered pool has been repaired and linked into the same system.

The overgrown yews which overshadow the garden are being steadily trimmed back to allow light again and a replanting program commenced. Grass snakes as well as a multitude of frogs, newts and other pond life multiply, and even Adders have been sighted again whilst birds multiply.

There was one last surprise; the winter and spring of 2013 -14 were extraordinarily wet for an area noted for its dryness – even compared with immediately surrounding villages. The garden began to flood – not from waters flowing into it, but because the ground itself was saturated. The normal ground water level in the immediate vicinity was at about 36 feet, but in this period rose to within 5½ feet of ground level, and the centre of the garden was under some 9 feet of water for nearly three weeks before receding – by then to the dissatisfaction of a family of ducks who had taken up residence. The trees and shrubs proved to be unaffected. The evidence of records and from village memory was that this was unprecedented.

Although the basic content and materials of the Pulham execution remain, the nature of the garden has changed from being a substantial excavation – but fully open with a slope upwards to the South – to one which is now contained on all sides by walls of rock and greenery to the point that it has acquired an air of secrecy due to its presence being completely hidden and obscured until the entrance gate is opened. Not perhaps William Oxenden Hammond’s idea of a garden, but one with which certainly the later Pulhams 38 would be well pleased .

Peter Hobbs

END NOTES

1. E.Hasted, The History and Topographical Survey of the County of Kent,2nd ed., ix (1797-1801), 251-262.

2. MSS. A vellum bound notebook, 8 1/4 x 6 1/2in. The front cover is headed : MSS Family Histories, above which is written: This Book contains a good deal of broken family history commenced by my grandfather William Hammond & continued by my father William Osmund Hammond, & further by myself Wm Oxenden Hammond. The book was in the possession of the late Mrs Peta Binney, the elder grand-daughter of Mrs Selina Hammond, wife of Egerton Hammond who was last in the direct line of Hammonds. John Newman in Kent: North East and East (2013 ) 470-472 provides a description of both houses.

3. Jill Allibone, George Devey, Architect, 1828-1886 (1991); British Architectural Library, Geo Devey 125,56-57.

4. Photograph c1870 provided by the late Mrs Pete Binney in possession of the writer.

5. Jill Allibone, Op cit. Keith Parfitt, Anglo Saxon Cemetery at Nonington; Kent Archaeological Review 147 ,154-157.

6. CKS, U442 P30.

7. KAS Archive of Past Members Box 28 Transcription of rental information for the Manor of Essole 1501. The reference is to a Borsate Pit which, as far as we can determine, means a pit below the brow of a rise which accurately describes the position before the College constructed student accommodation and altered the lie of the land.This appears to be a large pocket of brick earth in an area which is otherwise solid chalk so it could be that brick earth was already being extracted for brick making. The fireplace and chimney in the Hall of Old St Albans Court are dated to this period so this could be the evidence for the start of what became a substantial local industry.

8. Peter Hobbs, Old St Albans Court Nonington, Arch Cant CXXV 2005, endnote 50.

9. Op cit. The Dover Archaeological Group have since excavated brick clamps dated to the 1660s approximately150 yards to the West. In this area, there is no chalk but brick earth of what appears to be excellent quality from the limited trials carried out by the Dover Archaeological Group.

10. Op cit

11. Noted by the owner in 2000.

12. MSS op cit.

13. Photograph op cit

14. Ordnance Survey 1872, 25 in to the mile, 1sted.

15. Allibone op cit

16. Durability Guaranteed – Pulhamite Rockwork – Its conservation and repair; English Heritage 2008, App A; A Gazetteer of Pulham sites.

17. Allibone op cit 55-56.

18. Durability Guaranteed op cit. London Landscape No 20, 2000, London Parks and Gardens Trust. Claude Hitching, The Pulham Legacy, Hertfordshire Countryside 2004. Claude Hitching found whilst researching his family tree that no less than five of his direct ancestors had worked for the firm of Pulham and this persuaded him to research the firm and its activities directly and publish the definitive work on the activities of his forbears which in turn generated the interest for the rediscovery of many more forgotten works.

19. Durability Guaranteed op cit.

20. Op cit.

21. John D. Woods Co. Residential and agricultural Estate of St Albans Court, Nonington, 1938, 24.

22. Durability Guaranteed, A Gazetteer of Pulham sites.

23. As related to the author by Ian Sayer, the last Head Groundsman for Nonington College whose grandfather was noted on the In Memoriam note of 1903 as one of the gardeners who had prepared the burial vault at Nonington Church for William Oxenden Hammond. His father and his uncle were also later employed as gardeners on the estate and one or other of these would have warned off the young Hammond sisters. See Note 26. It is suggested that this form of transport was remembered because old fashioned horses were used rather than agricultural traction engines.

24. Peter Jeens, Geologist, Meetings Secretary, Kent Geological Group.

25. As shown to the author by Aubrey Sutton, the Head Caretaker for Nonington College who lived in the cottage adjoining the sunken garden and who, as a child, had played there, as had in turn his children. His daughter remembered being in constant trouble for going home coated in duck weed from the pools which remains a problem despite our cleaning efforts, presumably being reseeded constantly by the numbers of birds that bathe and drink there.

26. By the author.

27. This very substantial piece of work was organised by Richard Hosking aided by Graham Hartley, Les Moorman, Donna Lambert, Barry Sheridan and Marie- Charlotte Wahl. This may be the only Pulham garden which has ever been surveyed.

28. Some of the walls were concave structures to hold back earth but in other cases, convex, possibly for planting beds. Ends were unfinished and simply tapered off into the earth banks. The bricks are yellow machine bricks, presumably from Sittingbourne Brick Fields and were visible. Yet Devey had used locally hand made red brick for his 1869 Stables and was using vastly more for the new Manor House and all the terracing there. Was he not interested or was the Pulham contract entirely separate? Hammond must have been content or he would have surely changed it : after all, he had no qualms in making vastly greater changes to the old house.

29. As related to the author in a letter from the late Mrs Peta Binney, Mrs Ina Hammond’s elder grand-daughter.

30. Aubrey Sutton op cit.

31. As related by a number of former students to the author. Ian Sayer op cit.

32. Nonington College Kent, England 1938-1986 Edited by Judith A Chapman and Jean M Whittles 2004. Newspaper cuttings from the 1960s in the Aubrey Sutton Collection. The College was the first to award degrees for dance and became a major source of PE Teachers.

33. By Gareth Daws, Stone worker and archaeologist, and the author. This included an assessment of the amount of rock at the St Albans house. The survey of the garden revealed quantities of rock in situ not previously observed in any detail.

34. From the Aubrey Sutton Collection.

35. Nonington College op cit.

36. James Pulham, Picturesque Ferneries, and Rock-Garden Scenery, in Waterfalls, Rocky Streams, Cascades, Dropping Wells or Cavernous Recesses for Boathouses, &c, &c, Penfold and Farmer , London 1877; Appendix.

37. Do go and see the Grade 1 listed Pulham surprises at the labyrinth at Dewstow Gardens & Grottoes at Caerwent in Monmouthshire! Or the waterfall on the cliffs at the centre of Ramsgate Harbour front.

Appendix 1 – Survey of Pulham Garden

Appendix 2 – The Plants in the Dell, St Alban’s Court Nonington

Richard and Mary Hoskins

The first known reference to the rock garden at St Alban’s Court, Nonington appears in a promotional booklet published circa 1877 by James Pulham II (Pulham, c.1877). In the appendix of the booklet Pulham lists

“… a few of the most choice, hardy plants, shrubs, conifers, and flowers …. I find that many want to know what plants are most suitable …… not for professional and experienced gardeners” (Pulham, c.1877).

This list of trees, shrubs, ferns, climbers and herbaceous plants is quite comprehensive and includes more than 400 named species or varieties, as well as referring more broadly to families of plant used in gardens designed by the Pulham family. Each Pulham garden would have included a selection from this list, varying in number according to the size of the garden. The rock garden at Nonington, now known as ‘The Dell’, is not large and the selection of plants would therefore have been relatively modest.

A general survey of the plants currently growing in The Dell was carried out during several visits during 2012 and 2013. Seventy-five species of plant were identified and listed during these visits (see Appendix 1 below), excluding known recent additions. Comparing this list with Pulham’s list produced 30 matches of plant species or families.

After more than 140 years a low number of matches would not be surprising, especially as the garden went through a 60 year period of neglect during the 20th century, so at first sight 30 matches seems quite a high number. Included in this total are seven species of large tree, including three varieties of yew, Common Yew (Taxus baccata), Golden Yew (Taxus aurea) and Irish Yew (Taxus fastigiata); two of Cypress (Cupressus lawsonii and one other), one of Spruce (Picea) and one of Holly (Ilex aquifolium). Yew is slow growing, and it is quite possible that the three species were all introduced by Pulham. Cypresses grow relatively quickly, and if these species were planted at Nonington by Pulham, it is perhaps more likely that the existing trees are descendants of the originals. On the other hand, the Spruce (probably Picea abies or Norway Spruce) is a large tree that is prominent in photographs of the Dell taken in the 1960s, so might therefore be original. The Pulham plant list includes variegated hollies and dwarf rock holly but does not specifically mention Common Holly (Ilex aquifolium), of which several mature specimens are now found in the Dell.

There are four species of smaller tree, or shrub, common to both lists. These are: Spotted Laurel (Aucuba japonica variegate), Deutzia (probably Deutzia crenata), Elder (Sambucus nigra) and Common Dogwood (Cornus sanguinea). The last two are species which occur locally in the wild and are immature specimens which have probably been introduced recently and naturally.

Any rock garden worthy of the description would be incomplete without a selection of ferns. All five species of fern now growing in the Dell are found on Pulham’s list. These are Royal Fern (Osmunda regalis), Hartstongue Fern (Asplenium scolopendrium), Common Polypody (Polypodium vulgare), Prickly Shield Fern (Polystichum aculeatum) and Male Fern (Dryopteris filix-mas). Most of these ferns grow locally in the wild, but it is very likely that all were included as part of the range introduced into the Dell by Pulham. Of particular note is the Royal Fern which has now become rare in Britain as a result of wetland drainage but survives in profusion in the Dell.

Pulham includes a separate list of climbing or trailing plants . . .

“. . Suitable to grow up, or trail down, especially over the thick strata of the rocks” (Pulham, c.1877).

Remarkably few different climbers or trailers survive in the Dell. Of those which do, by far the most abundant is Ivy. Pulham recommends obtaining ivies, including . . .

“. . very good small Ivies…. from the banks and hedges, growing wild” (Pulham, c.1877),

. . and there is no reason to suppose that the ivies in the Dell did not arrive in this way, as most appear to be Common Ivy (Hedera helix). One patch of Ivy has exceptionally large leaves – up to 20cm in length – and may represent a less common variety. Of the other climbing or trailing species currently found in The Dell, three, Rock Cotoneaster (Cotoneaster horizontalis), Pheasant Berry (Leycesteria Formosa) and Honeysuckle (Lonicera periclymenum) are all included in the Pulham list but all could easily have been introduced naturally.

The remainder of the plants currently growing in The Dell consist of at least 46 different species of flowering herbaceous plant, of which eleven are also included in the Pulham Plant List. Some of these are common species of locally found wild flowers such as Bugle (Ajuga reptans), Wild Arum (Arum maculatum), Ground Ivy (Glechoma hederacea), Primrose (Primula vulgaris), and Dog Violet (Viola riviniana). Two others, Common Ragwort (Senecio jacobaea) and Babies Tears (Soleirolia solierolii) are species that were introduced to Britain as garden plants during the nineteenth century, and have since become notorious invasive plants. These may therefore be remnants of Pulham’s original planting. Four further flowering plants may also be descendants of the Pulham planting: Acanthus (Acanthus montanus), Autumn Cyclamen (Cyclamen coum), Small-leaved Periwinkle (Vinca minor) and Shining Crane’s Bill (Geranium lucidum). The last-named is widespread in The Dell with its striking, bright pink flowers and dark green, glossy leaves.

There are several plants that grow prolifically in The Dell but which are not named in the Pulham list. Solomon’s Seal (Polygonatum biflorum) is an uncommon wild flower of the local Kentish woodland which is also often grown as a garden plant, flowering in the early spring. Yellow Archangel (Lamiastrum galeobdolon) is another wild plant also common in gardens, the species growing in The Dell being the silver-leaved variety. Finally, a very striking plant in The Dell is Indian Rhubarb (Darmera Peltata), a native of North America which grows as thick, spreading rhizomes in the wet and boggy areas at the bottom of The Dell and produces metre-tall inflorescences of five-petalled bright pink flowers in late spring. These are followed by even taller stems bearing large, round, green leaves that give the plant its common name and which turn deep red in the autumn. Despite their absence from his list it would not be surprising if Pulham had introduced one or more of these three plants to the Dell.

In conclusion, the 30 species of plant currently growing in The Dell that are also included in the Pulham list of c.1877 are unlikely to be all original Pulham plants or even direct descendants thereof. It is probable that most of the smaller shrubs and herbaceous plants have not survived to the present day and that similar species have been planted and re-planted since then. Some of the original conifers may well have survived, together with a handful of ferns, a few shrubs and climbers, and a small number of the more tenacious flowering plants. Apart from these few remaining plants, the Pulham legacy is contained in the rockery itself which remains as an oasis of 19th century gardening endeavour which can still be appreciated in the 21st century.

References:

Pulham, James c1877, Picturesque Ferneries and Rock-Garden Scenery, in Waterfalls, Rockystreams, Cascades, Dropping Wells, Heatheries, Caves or Cavernous Recesses for Boathouses,

&c, &c. Broxbourne and Brixton: James Pulham & Son (Lindley Library, RHS)

Appendix 3 – Chronological Gazetteer of Pulham Sites in Kent

Sources: Rock Landscapes ,The Pulham Legacy, Claude Hitching , Garden Arts Press 2012 ; Pulham Legacy Newsletters at http://www.pulham.org.uk; Durability Guaranteed, English Heritage,2008. Viewable – *

1854-6 Broomhill, Tunbridge Wells Rocky pass and banks

1860 F.Wilson, Tunbridge Wells Fernery, cliff to bank.

1862-4 Dunorlan Park, Tunbridge Wells Substantial works. *

1865-70 Civic Centre ,Bromley Some rockwork *

1866 J.Stewart,West Wickham Fernery.

1867 J.Batten, Bickley Fernery.

1867-9 Rosherville Gardens, Gravesend Cavern with Dropping Well.

1868-80 Court Lodge, Lamberhurst Substantial works.

1870 Staplehurst Hall, Staplehurst Rocks on lake margins.

1870 Barham Court, Canterbury Dropping Well and pool.

1870s Roydon Hall, Yalding Fernery and Dropping Well .

1873-4 Sundridge Park, Bromley Chasm, Fernery, Cliff. ? *

1874-5 J. Ridgway,Goudhurst Fernery.

1875 Preston Hall,Maidstone Unknown

1876 Downham, Bromley Fernery.

1877 St Albans Court, Nonington Fernery and rocky banks.

1894 Madeira Walk, Ramsgate Substantial works. *

1897 Beechy Lees, Rochester Rock works.

1910 Lower Leas,Folkestone Caves. *

1912 Marl House, Bexley Water and Rock Garden.

1914 Penchullee,Bromley Unknown.

1920-21 The Leas, Folkestone Substantial works. *

1923-36 St Lawrence, WestCliff, and

Winterstoke Gardens, Ramsgate Substantial works. *

? Colesdane, Harrietsham Unknown.

There are other unidentified sites in Kent known only by the name of the customer or the town. Hundreds of sites of Pulham work exist across the country, many still viewable.