9th September, 1940-a Hurricane lands in Nonington

The Battle of Britain was a major air campaign fought largely over southern England in the summer and autumn of 1940. After the evacuation of the British Expeditionary Force from Dunkirk and the Fall of France in June of 1940, Germany planned to gain air superiority in preparation for an invasion of Great Britain. From the following July heavily outnumbered R.A.F Fighter Command pilots of many nationalities flew Hurricane and Spitfire aircraft against daily waves of German Luftwaffe aircraft. The R.A.F pilots inflicted heavy casualties on the Luftwaffe and in October of 1940 the Germans finally conceded defeat, forcing Adolf Hitler to abandon his invasion plans. Many of these encounters took place in the skies over East Kent.

On 9th September, 1940, at 07.00.hrs an R.A.F Mark I Hurricane, registration number P3610, crash landed in Nonington. I believe the site of the landing was in the fields in the valley bottom to the west of houses in Church Street. The aircraft was piloted by Pilot Officer Leonard Charles “Elsie” Murch of No 253 Squadron, who escaped injury. His squadron was at the time based at Kenley near Croydon in Surrey, Information regarding the crash landing is scanty, but it appears he was making a forced landing when the aircraft’s engine cut out. Possibly the forced landing was brought about by damage to the Hurricane sustained during an engagement with German aircraft.

A month or so later P.O. Murch suffered a broken arm on 11th October when he was forced to bale out of another Hurricane, registration number V6570, during an engagement with German aircraft over Tunbridge Wells.

The Hawker Hurricane first went into service in 1937 and was the first R.A.F aircraft to fly over at 300 m.p.h. During the early part of the Second World War the Hawker Hurricane became well known as an effective workhorse, and during the Battle of Britain the Hurricane is credited with a success rate in combat against German aircraft of three or more times higher than that of the better known and more glamorous Spitfire. A total of 1,715 Hawker Hurricanes flew with Fighter Command during the period of the Battle of Britain, making a total of thirty-two squadrons compared to nineteen squadrons of Spitfires.

P.O. Murch survived the Battle of Britain and in July of 1941 he joined 185 Squadron in Malta. He then went to the Middle East in 1942 and in 1943 was serving with 680 Squadron, a photographic-reconnaissance unit. On 16th September of 1943 he sadly died in the R.A.F Hospital at Benghazi after contracting poliomyelitis and he is buried in Benghazi War Cemetery in Libya.

++++++

13th June, 1944-a Doodlebug drops in on Nonington

As the Second World War progressed the Allies gradually began to gain the upper hand and were able to relentlessly bomb German cities. In order to try and regain Germany’s lost advantage Adolf Hitler and ordered the use of “vengeance weapons” (Vergeltungswaffen) for use against London in an attempt to terrorise British civilians and undermine their morale.

Click on here to view

The Imperial War Museum’s

The V1 Flying Bomb: Hitler’s vengeance weapon

The first of these V weapons to come into widespread use was the V1 Flying Bomb, more widely known as a ‘buzz bomb’ or ‘doodlebug’ because of the noise their engines made. Once launched the V1 flew in the direction it was pointed until it ran out of fuel and then fell to the ground and exploded on impact.

V1 launches began a week after the Allied landings in Normandy on 6th June, 1944, with the first V1’s hitting London early in the morning of 13th June, 1944, and what became known as “The Doodlebug Summer” quickly followed. At its peak there were over two hundred V1’s launched daily, but by the end of August the majority of rockets were failing to reach the capital as coastal air defences and the R.A.F became more adept at downing them.

They were initially launched from the Pas-de-Calais area on the northern coast of France and the Dutch coast, but the launch sites later moved inland as the Allies advanced into France, Belgium and The Netherlands.

It was one of these first day V1’s that fell into the field behind the Youth Club in Easole Street at 23.55.hrs on 13th June, 1944. I can be precise with the date and timing as I found this information written on one of the wooden beam in the old 1704 malthouse during a visit there before it was converted into a dwelling. A photograph was taken of the inscription, but unfortunately it is not clear enough to make it worthwhile posting a copy.

The exploding doodlebug left a large crater, usually they were some thirty or so feet wide and six feet or more in depth, in the field that was later filled in. Many of the trees alongside the Leafy Lane footpath, also known as Sleigh Lane across from the Royal Oak were peppered with shrapnel. This shrapnel later caused minor problems when some of these trees were later felled. Presumably the explosion also shattered the windows of the few houses that then backed onto the field.

Some pieces of the doodlebug survived the explosion and were kept as mementos.

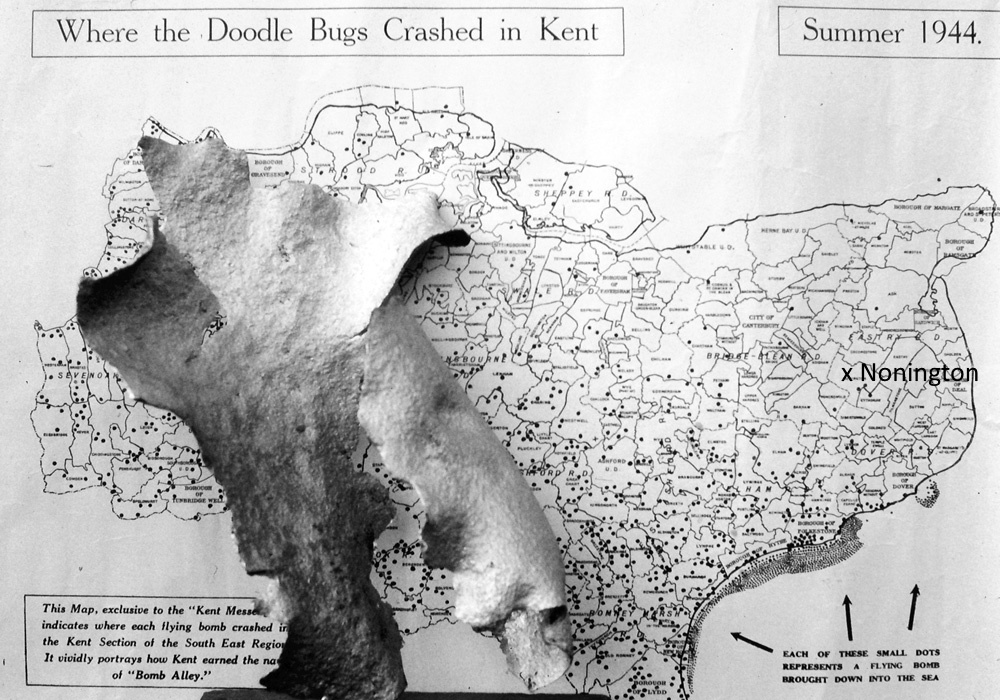

One such piece of shrapnel is shown in the picture below. It has been placed on a copy of a map of “Where the Doodle Bugs crashed in Kent” published in “The Kent Messenger” in September of 1944. Fortunately for its inhabitants Nonington was on the extreme eastern edge of what was called on the map “Bomb Alley” and the vast majority of V1’s fell on West Kent.

My late mother, Joan Webb, lived in Aylesham during the war years and she told me it was quite frightening to hear the distinctive sound of doodlebug flying towards you, especially at night. Mum recalled that you hoped that it would keep flying on but wishing that meant you felt guilty as you knew it was then possibly going to drop on somebody else. She said that when the engine began to stutter you knew it was soon going to fall and when the jet engine cut out there followed an eerie silence as the rocket fell to the ground and then exploded.

The time from the engine cutting out to the doodlebug hitting the ground was around fifteen seconds. Usually the rocket dived straight into the ground, but at other times it would glide for some considerable distance before crashing and exploding.

My mother also recounted how she sometimes saw R.A.F. planes shoot down incoming V1’s and blow them up in the air, and that some pilots would actually fly alongside the doodle bugs and tilt them off balance by putting their plane’s wing tips under the side fins of the rocket. Apparently the pilots did not touch the V1’s wing, the disturbance in the airflow caused by the aircraft’s wing underneath the V1’s wing was enough to interfere with the airflow and affect the V1’s gyroscope enough to slightly alter its course causing it to change direction or crash.

Click on here to view

The Imperial War Museum’s

The V1 Flying Bomb: Hitler’s vengeance weapon