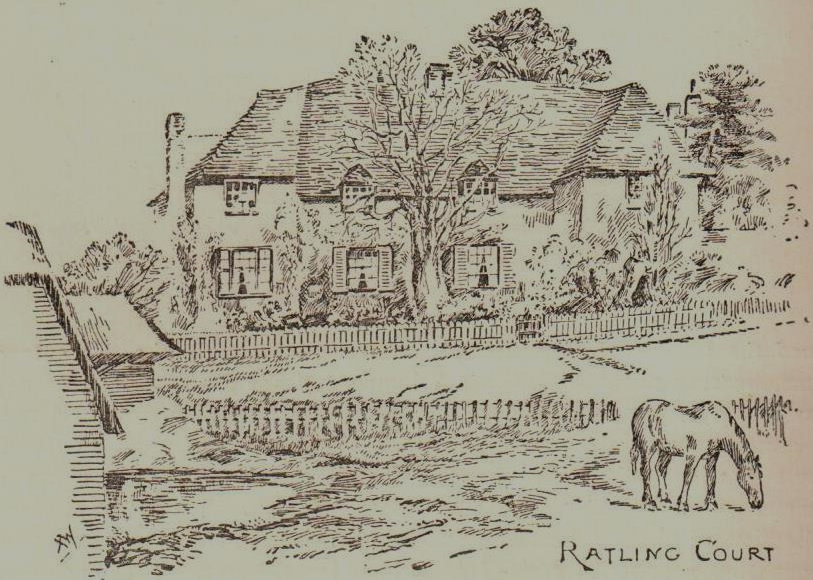

Ratling Court is a manor house that evolved over the centuries and contains elements of several periods. The centre of the house is the oldest part, originally the open hall of an aisled house dating from the early 14th century,or possibly before whilst the north wing was rebuilt with an upper floor in the mid-15th century. William Cowper rebuilt the southern wing, which is dated 1637, and also added the great fire place and the upper floor in the old hall. A century or so later a Georgian room was built at the rear of the house along with the brew house at the north end of the house which has a thatched donkey wheel house for drawing water from the well.

The Manor of Ratling: A brief history:

The name Ratling is said to derive from the Old English (O.E.). ryt hlinc; literally a rubbish slope which was an area of little use for agriculture. The knight’s fee of Ratling was in the far northern corner of the old parish of Nonington, bounded by the Wingham road to the west, the Goodnestone estate to the north and the old Curleswood Park, now Aylesham village, to the south.

Pre-1093-the name Ratling suggests a Saxon foundation but the earliest documentary reference was in 1093 when Godfrey de Retlyng is recorded as holding a knight’s fee of the Archbishop as part of the Manor of Wingham.

1171-Alan de Retlyng held the fee.

1196 Estretling, 216 acres, sold to Thomas de Retling (indicating that Estretling was either a separate fee or part fee or that the original knight’s fee of Retlyng had divided at some time previously).

1210-Thomas de Ratlynge recorded as possessor.

1213-the estate appears to have been divided in the early 13th century into Retlyn and Estriteling (now Old Court).

It appears to have briefly become one fee again as a roll of knight’s fee made in 1254 recorded Heres de Retlinge, literally meaning the heir to Retlinge, as holding a knights fee, but after this date Ratling and Estriteling owed half a knight’s fee each indicating the original knight’s fee had been divided again between two holders.

1279-Richard de Dovers acquired half a fee in Ratling, and from then onwards was referred to as Richard de Ratlinge. On 18th July 1279 Ralph Perot did “homage and fealty” to Archbishop Pecham for half a knight’s fee at Ratling.

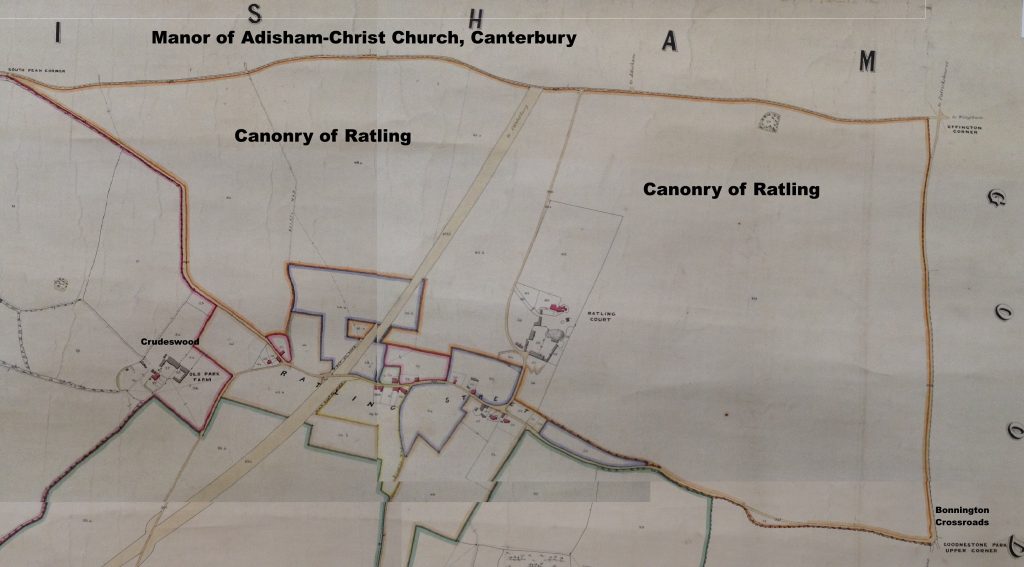

1286-Archbishop Peckham founded his College of Secular Canons at Wingham and granted to the Canonry of Ratling, later the Ratling Court estate, the tithes of: “the land that Richard de Ratling and Ralph Perot hold of the Archbishop between the highway which leads from Crudeswood (Curleswood Park Farm), to the cross (cross-roads) at Bonnington, and thence to the estate of the Priory (of Christ Church, Canterbury) at Adesham (Adisham)”. Some of the Canons houses can still be seen in Wingham next to The Dog Inn.

The Manor of Ratling. The Canonry received the tithes of the land defined by the gold line on the 1859 Poor Law Commissioners map

1309-John de Retlynges did “homage and fealty” on 25th November to Archbishop Robert Winchester for half a fee at Ratling whilst the Archbishop was staying at his Wingham Manor House.

1325-Laura de Ratling became Abbess of Malling Nunnery, at West Malling in Kent, which had been founded by Gundulph, Bishop of Rochester between 1087-89.

1344-Thomas de Ratling was ordered by the King’s representative to collect the wool subsidy, but the Prior of Christ Church Monastery, Canterbury, where Thomas was an official, wrote to the Archbishop of Canterbury asking him to intercede and get Thomas released from this duty as he was a useful servant of the monastery.

1347-Across the Kingdom assessments were made for: “Aid to Knight the Black Prince”. In its strictest application the “Aid” referred to the assessments levied upon holders of knight’s (military) service of the Sovereign or other lord for special national occasions or purposes. Thomas de Ratling and the Abbot of Langdon were jointly to contribute 20 shillings and the heirs of Saire (Sarah ?) de Retling and Margery, her sister, were to give 40.s. (£.2.00). “De heribus Saire de Retlynge et Margerie sororis sue pro vno feodo quod predicta Sarra et Margeria tenuerunt in Ritlynge, de eorden Archiepiscopo ..Xl.s”.

1350-Sir Thomas de Retling died in possession of Ratling, 23, Eduard III.

1356-Thomas de Ratling mentioned in documents, 29, Eduard III.

1387-Sayer de Ratling died, leaving an only daughter, Joan

1431 John Fynes (Fyneux), gentleman, held Retlynge in the county of Kent for three parts of a knights fee. At the same time a yeoman called Hunter also held land at Retlynge.

1453 a feet of fines dated 27 January 1453 (54)] records that Thomas Isaak’, esquire, bought the manor of Ratlyng from John Fyneux, esquire, and Joan, his wife.

1502-James Isaac, deceased, had held Ratling but had enfeoffed one quarter of it to his own use, and three-quarters as jointure for his daughter-in-law, Benedicta, the daughter of John Guldeford, Knight. This three-quarters was worth £.6.00 and gave 12d (5p) a year to the Archbishop in his Wingham manor, whilst the quarter, lately John Hall’s, was worth 43.s 4d. (£2.17 pence) and gave the Archbishop 12d. Both parts of the manor were held by knight’s service.

1525-Around this date Edward Isaac sold his Ratling property to Sir John Fineux, Chief Justice of the King’s Bench, who died in 1526, and whose son, William Fineux, later alienated (transferred) it to Thomas Engeham, Gent., of Goodnestone.

1558 to 1628-Thomas Engeham’s will left Ratling to Edward, his second son, whose own son, William Engeham, sold it to William Cowper, Esq., the first of the Cowpers (pronounced Cooper) to own Ratling Court. William left a quantity of interesting documents, amongst which were his 1628 plans to convert the house to two stories and to extend it stating that the building was in a very sad state and hardly worth renovating.

1637 to 1664-William eventually carried out some renovation work which included rebuilding the south wing, which is dated 1637, but the resulting building was only half the size he had originally planned. Charles I made him a Baron of Nova Scotia and then later, in 1642, a baronet of Great Britain.

A staunch supporter of the King he was imprisoned by during the English Civil War but on the Restoration of Charles II William’s honours and estates were restored to him before his death in 1664. His eldest son William, succeeded him to the baronetcy and went on to became a distinguished lawyer.

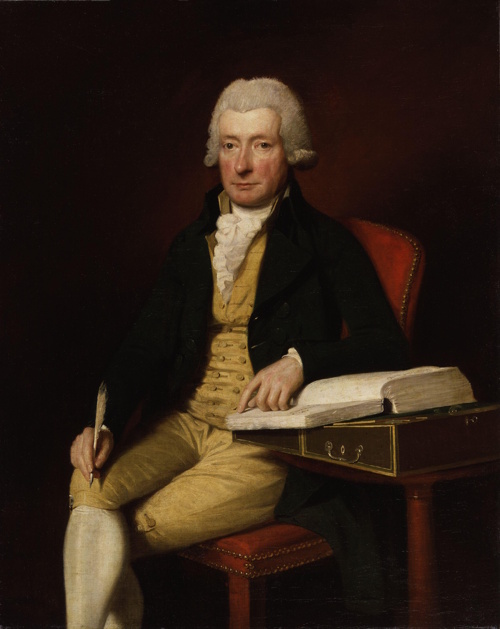

William Cowper, held by many to be the foremost poet of the generation between Alexander Pope and William Wordsworth.

A 1792 portrait by Lemuel Francis Abbott

Spencer Cooper, a younger brother, was the grand-father of another William Cowper, the English poet and Anglican hymn writer held by many to be the foremost poet of the generation between Alexander Pope and William Wordsworth and a forerunner of Romantic poetry. For several decades Cowper probably had the largest readership of any English poet, and he changed the direction of 18th-century nature poetry by writing of everyday life and scenes of the English countryside. Samuel Taylor Coleridge called him “the best modern poet” and William Wordsworth held his unfinished poem “Yardley-Oak”, written in 1791, in high regard.

William Cowper the lawyer was educated at St Alban’s School, and was called to the bar in 1688; having promptly given his allegiance to the Prince of Orange on his landing in England, he was made recorder of Colchester in 1694. William enjoyed a large practice at the bar, and had the reputation of being one of the most effective parliamentary orators of his generation. He lost his seat in parliament in 1702 owing to the unpopularity caused by the trial of his brother Spencer on a charge of murder.

Appointed Lord Keeper of the Great Seal in 1705 he took his seat on the Woolsack without a peerage. The following year William conducted the negotiations between the English and Scottish commissioners for arranging the union with Scotland. In November of the same year (1706) he succeeded to his father’s baronetcy; and on December 14th, 1706, he was raised to the peerage as Baron Cowper of Wingham, Kent.

When the union with Scotland came into operation in May 1707 the Queen in Council named Cowper the Lord High Chancellor of Great Britain, the first to hold this office. He presided at the trial of Dr. Sachaverell in 1710, but resigned the seal when Harley and Bolingbroke took office in the same year. On the death of Queen Anne in 1714 and his succession to the throne George I appointed Cowper one of the Lords Justices for governing the country during the King’s absence, and a few weeks later he again became Lord Chancellor. Cowper supported the impeachment of Lord Oxford for high treason in 1715, and in 1716 presided as Lord High Steward at the trials of the peers charged with complicity in the Jacobite rising of 1715 where his sentences were censured as unnecessarily severe. He warmly supported the Septennial Bill in the same year.

On March 18th, 1718, Sir William was created Viscount Fordwich and Earl Cowper, and a month later he resigned office on the plea of ill-health, but probably in reality because George I accused him of espousing the Prince of Wales’s side in his quarrel with the King. Taking the lead against his former colleagues, Cowper opposed the proposal brought forward in 1719 to limit the number of peers, and also the Bill of Pains and Penalties against Atterbury in 1723. In his last years he was accused, but probably without reason, of active sympathy with the Jacobites. He died at his residence, Panshanger in the village of Cole Green, built by himself in 1723.

1718 to 1971

“The Ratling Fireball:– On December 11, 1741, a fire-ball appeared soon after noon-day, and the sun shining, but few people saw it, and they could only guess at its course; which, however, was observed to be from north-west by north, to south and by south, and right over Littleborne from Westbere, and towards Ratling, near which place lord Cowper, who was hunting, heard but one explosion (for there were two); the other most probably happened at such a distance, as to be in one with that so near him. Mr. Gostling, of the Mint yard, who gave the account of it to the secretary of the royal society, says, that he found his house violently shaken for some seconds of time, as if several loaded carriages had been driving against the walls of it, and heard a noise at the same time, which he took for thunder, yet of an uncommon sound; though he thought thunder, which could shake at that rate, would have been much louder, therefore he concluded it to be an earthquake; the sky, he found, was cloudy, but nothing like a thunder cloud in view, and there was a shower of rain from the eastward presently after, the coldest that he ever felt”.

The “Ratling Fireball” was almost certainly ball lightning, an unexplained atmospheric electrical phenomenon and observers of it frequently refer to luminous, usually spherical objects, which vary in size from pea-sized to several meters in diameter. It is usually associated with thunderstorms but the phenomenon often lasts considerably longer than the split-second flash of a lightning bolt. Many historical reports refer to the ball exploding, often with fatal consequences to persons and livestock, and leaving behind the lingering odour of sulphur.

William Hasted mentions Ratling in his chapter about Nonington in The History and Topographical Survey of Kent, volume IX, published around 1800.

“The MANOR OF RETLING, usually called Ratling, in that part of this parish adjoining to Adisham, which was antiently held of the archbishop by a family of the same name, who bore for their arms, Gules, a lion rampant, between an orle of tilting spears heads, or, as they were on the surcoat of Sir John de Ratling, formerly painted in one of the windows of this church, in which it continued down to Sir Richard de Retling, who died possessed of it in the 23d year of king Edward III. leaving a sole daughter and heir Joane, who marrying John Spicer, entitled him to it. After which, by Cicely, a daughter and coheir of this name, it passed in marriage to John Isaac, of Bridge, who died possessed of it anno 22 Henry VI. and his descendant Edward Isaac, esq. in king Henry VIII.’s reign, alienated it to Sir John Fineux, chief justice of the king’s bench, whose son William Fineux, esq. of Herne, alienated it to Thomas Engeham, gent. of Goodneston, who by his will in 1558, gave it to his second son Edward, and his son, William Engeham sold it to William Cowper, esq. who afterwards resided here, and was first created a baronet of Nova Scotia, and then, in 1642, a baronet of Great Britain. His great-grandson Sir William Cowper, bart. was by Queen Anne, being then lord keeper of the great seal, created lord Cowper, made lord chancellor, and afterwards, anno 4 George I. created earl Cowper, and in his descendants, earls Cowper, this manor has descended down to the right hon. Peter Francis, earl Cowper, the present owner of this manor. There has not been any court held for it for many years past.“

The Earls Cooper had never had a residence at Ratling and by 1800 Ratling Court had become a farmhouse. The seventh Earl Cowper was Lord Lieutenant of Ireland from 1880 to 1882 and during his tenure in Ireland Punch Magazine said of him, “However a meagre court he holds at Dublin Castle he has a Ratling Court in Kent.

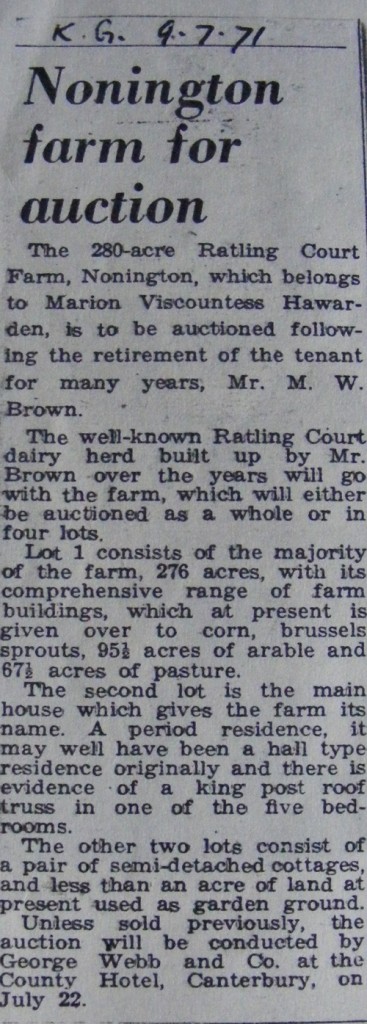

Ratling eventually passed from the Cowper family by marriage to William Henry Grenfell, 1st Lord Desborough whose son sold the property to Albert Leslie Wright of Butterley Hall in Derbyshire. The Wright family’s fortune came from The Butterley Company, which had many interests including, land; iron and steel works; coalmines; and brickworks. Albert Wright’s first wife was Margaretta Agnes Plumptre, daughter of John Bridges Plumptre and Elizabeth Wright, and their eldest daughter, Marion, married Eustace Wyndham Maude, 7th Viscount Hawarden, in 1920. Ratling Court was one of several neighbouring farms given to the couple as a wedding present by the bride’s father. The 7th Viscount died in 1958 and Ratling Court was sold by Marion, Viscountess Hawarden in 1971.

I do refer to Rytlinge on the Nonington Place Names page in the section for Ratling. The reference to a subordinate church or chapel at Rytlinge, attributed by Dr. Ward as being Ratling, is a mystery as I have yet been unable to find another reference to a church or chapel at Ratling. However, the present archaeological excavations at Aylesham made possible by the ongoing building of new houses there may uncover evidence confirming the location of a chapel or church. That is providing that the excavations are ever written up and published. Up until now the only reports of the excavations appear to be old press releases.

This link to to a very informative work on early lists of parish churches in Kent may be of interest to you. https://www.durobrivis.net/survey/db-ke/08-churches.pdf

The notes and comments on Ward’s interpretation of the contents of the various bring to light errors by Ward. It’s therefore possible that Rytlinge is not actually the modern Ratling, but was mis-attributed by Ward.

A Saxon church in Ratling is mentioned in Archaeolgia Cantiana Volume 45 page 79. This is a translation of the Domesday Monachorum. The date of the Monachorum is uncertain but believed produced in the time of Lanfranc (1070-1089). Some say 1070, others 1089. This would be an early mention of Ratling.