During the English Civil War of 1642 to 1651 close neighbours, friends and even family members frequently took opposing sides in the conflict between the Royalists and Parliamentarians. These divisions were very obvious in Nonington and the adjoining parishes of Goodneston and Knolton as can be seen in the following article.

~~~~~~

The Boys Families of Fredville & Bonnington

~

Sir Edward Boys & Major John Boys of Fredville

Sir Edward Boys of Fredville became Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports and Governor of Dover Castle in 1642 and had initially held the castle for King Charles I, but that same year he went over to the Parliamentarians and continued to hold the strategically important castle, known for centuries as the Gateway to England, for Parliament until his death in 1646 when he was succeeded in the posts of Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports and Governor of Dover Castle by his eldest son, Major John Boys, who held these positions until 1648. Sir Edward was also M.P. for Dover in both the “Short” and “Long” Parliaments and was involved with several parliamentary commissions and boards including the New Model Ordinance to form the Parliamentarians New Model Army in 1645.

Sir Edward Boys had a younger son, also called Edward whose baptism on 14th December, 1606 is recorded in the Nonington parish register. The younger Edward Boys also supported and fought for the Parliamentary side and died of wounds received at the Battle of Keynton, otherwise known as the Battle of Edgehill. The parish register of Church of St. Nicholas in Warwick records: “Buried 22nd Jaunarie 1642 [1643] Edward Boyse ye sonne of Sir Edward Boyse of East Kent wounded at the Battell at Keynton”.

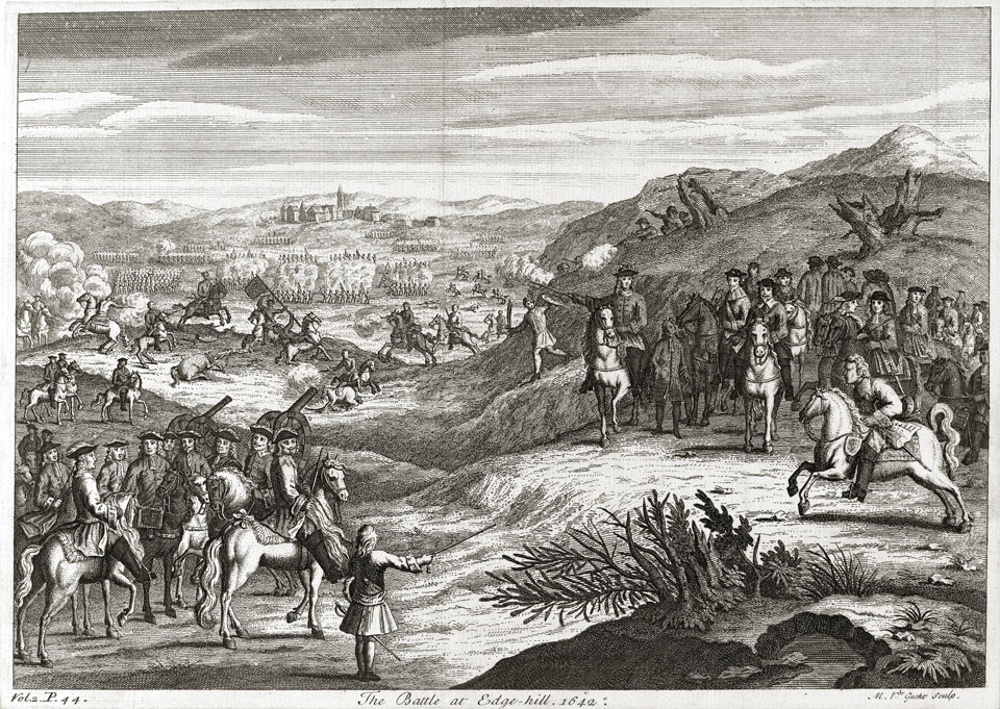

The Battle of Keynton, also Keyneton, [now Kineton in Warwickshire] was an alternative name for the Battle of Edgehill which was fought over the countryside between Edgehill and Keynton in southern Warwickshire. The fighting between the Parliamentary forces under the command of Earl of Essex and the Royalist army led by Charles I began on Sunday 23rd October. The main battle was fought on the Sunday but fighting continued until the following Tuesday morning when Prince Rupert of the Rhine, the King’s nephew and commander of the Royalist cavalry, led a strong force in a surprise attack against what remained of the Parliamentary forces baggage train at Keynton resulting in the deaths of many wounded survivors of the earlier fighting. After this attack the fighting ceased, but the battle had no clear winner. The Parliamentary forces withdrew to Warwick and reformed, while the King and his army continued on towards Oxford and then on to London.

The Battle at Edge-hill. Eraving by Michael van de Gucht, published in 1710. National Army Museum Online Collection

Colonel Francis Hammond, whose family estate of St. Alban’s Court in Nonington adjoined the Boys’ Fredville home, was in the Royalist army at Edgehill and led the Royalist’s Forlorn Hope, but whether or not the younger Edward Boys encountered Colonel Hammond during the battle is not known. The presence of immediate neighbours on opposing sides emphasises how the English Civil War divided the country, and, in the case of the Boys’, also families.

Edward Boys the younger appears to have been wounded during the fighting in and around Keynton and subsequently taken to Warwick. Here he was most likely treated for his wounds and hospitalized at Warwick Castle, along with some 700 or so others wounded in the battle. Sadly Edward succumbed to his wounds and was buried at St. Nicholas’s church on 22nd January, 1643. The church stands outside one of the gates of Warwick Castle, which indicates that he was in or near the castle when he died.

Confused identities often lead to errors in fact which are perpetuated over the centuries. This is certainly true in the case of Major John Boys of Fredville. William Hasted’s history of Kent record his having suffered severely for his Royalist sympathies in the English Civil War when in actual fact he was a Parliamentarian. His financial woes were caused because, according to William Boys’ 1802 biography and pedigree of the Boys family, ‘by his own extravagance he much encumbered and wasted the estate of Fredville’. Hasted and later historians confused Major John Boys of Fredville in Nonington with Sir John Boys of Bonnington, the famed defender of Donnington Castle, and a distant relative of the Boys’ of Fredville in Nonington. Bonnington is in the parish of Goodnestone and adjoins the northern boundary of the Parish of Nonington and was the original home of the Boys of Fredville in Nonington. Nonington, which in the past was often spelt Nonnington, Bonnington, and Donnington are only differentiated by their initial letter and could, and still can be, easily be confused.

Major John Boys of Fredville’s dedication to the Parliamentary cause was confirmed in 1645 when he was named as one of Parliament’s Commissioners and Council of War in Kent with “Power to Execute; Martial Law on all that have taken part in rising in Kent”. The task of the commissioners and the council was to restore law and order in the aftermath of a Royalist attempt to take Dover Castle and begin an insurrection in East Kent. During an earlier siege in 1642 Sir Edward and John Boys of Fredville had defended Dover Castle against a besieging force which contained at least one of the Hammond brothers from St. Alban’s Court, who were the Boys’ next-door neighbours. However, the English Civil War did not just set the Parliamentarian Boys’ of Fredville against their neighbours, they were also on the opposing side to their Royalist Boys kinsmen at nearby Bonnington and Uffington.

~~~

Sir John Boys of Bonnington

Portrait of Sir John Boys (1607-1664), half-length in armour, with a white lace collar, his coat of arms displayed in the top left hand corner inscribed

‘Sir John Boys. nat 1607/Governour [sic] of Dorrington Castle./for ye defence of wh. K Chs. 1st./granted to his coat of arms/a crown Imp.or on/a canton azure.’

Circle of William Dobson (1611-1646)

John Boys was the eldest son and heir of Sir Edward Boys of Bonnington and Jane, daughter of Edward Sanders of Northbourne. He was born at his father’s house at Bonnington in the Parish of Goodnestone-juxta-Wingham and baptised in nearby Chillenden Church on 5th April 1607. John was a distant kinsman of Sir Edward and John Boys of Fredville in the adjoining parish of Nonington where Sir Edward Boys of Bonnington held land.

The two John Boys’ are often confused with each other. One coming from Bonnington and the other from neighbouring Nonington, often spelt Nonnington, frequently confuses things to no small degree and the Bonnington Boys’ later renouned defence of Donnington Castle also adds to the general obfuscation.

The additional fact that both John Boys of Bonnington and John Boys of Fredville in Nonington also had fathers called Sir Edward Boys also further adds to the ongoing confusion over identities as to which John Boys was the Royalist and which one was the Parliamentarian during the English Civil War period. The Bonnington Boys, not the Nonnington Boys, was the Donnington Boys.

John Boys of Bonnington began his military career in the Low Countries where he served as a mercenary during the later part of The Thirty Years War and may possibly have served with Francis Hammond of nearby St. Alban’s Court in Nonington.

During the English Civil War, he became a captain in the army of King Charles I, and later served as Governor of Donnington Castle in Berkshire. At the outbreak of the Civil War in 1642 Donnington Castle was owned by John Packer, a Parliamentarian, and garrisoned by a Parliamentarian force, but was by then an out-dated structure and initially considered unimportant.

However, after Oxford became the Royalist capital after the King’s failure to capture London in the early months of the war Donnington Castle, which was located twenty miles to the south of Oxford on the main road to the north, gained strategic importance. The First Battle of Newbury was fought on 20th September, 1643, a mile or so to the south of the castle and resulted in a defeat for the Royalist army under the command of King Charles I. After the Royalist defeat Lt. Colonel John Boys with a force of 200 infantry, 25 cavalry and 4 cannon took possession of Donnington Castle and began the construction of substantial defensive earthwork.

By the summer of the following year Parliament forces had gained the upper hand and made attempts to open the road to Oxford by targeting the Royalist strongholds of Banbury Castle, Basing House, and Donnington Castle. Lieutenant-General John Middleton was sent with a force of 3,000 men to take Donnington. Middleton’s soldiers attempted a direct assault on 31st July which was repulsed with the attackers losing some 300 officers and men.

In late September Colonel Horton built a battery at the foot of the castle hill from where the castle was put under a constant bombardment. During a period of twelve days three of the fortification’s towers and a part of the wall were reduced to ruins by some 1,000 or so large cannonballs from the besiegers guns. When Horton received reinforcements, he offered terms of surrender to Lt. Colonel Boys, but Boys refused to accept them. Soon afterwards the Earl of Manchester and his forces joined with Horton but their joint efforts to end the siege proved unsuccessful.

After some two or three days of unsuccessful attacks the besieging forces gave up their efforts to capture the castle and withdrew after becoming aware that a relieving force led the King was en route for Donnington.

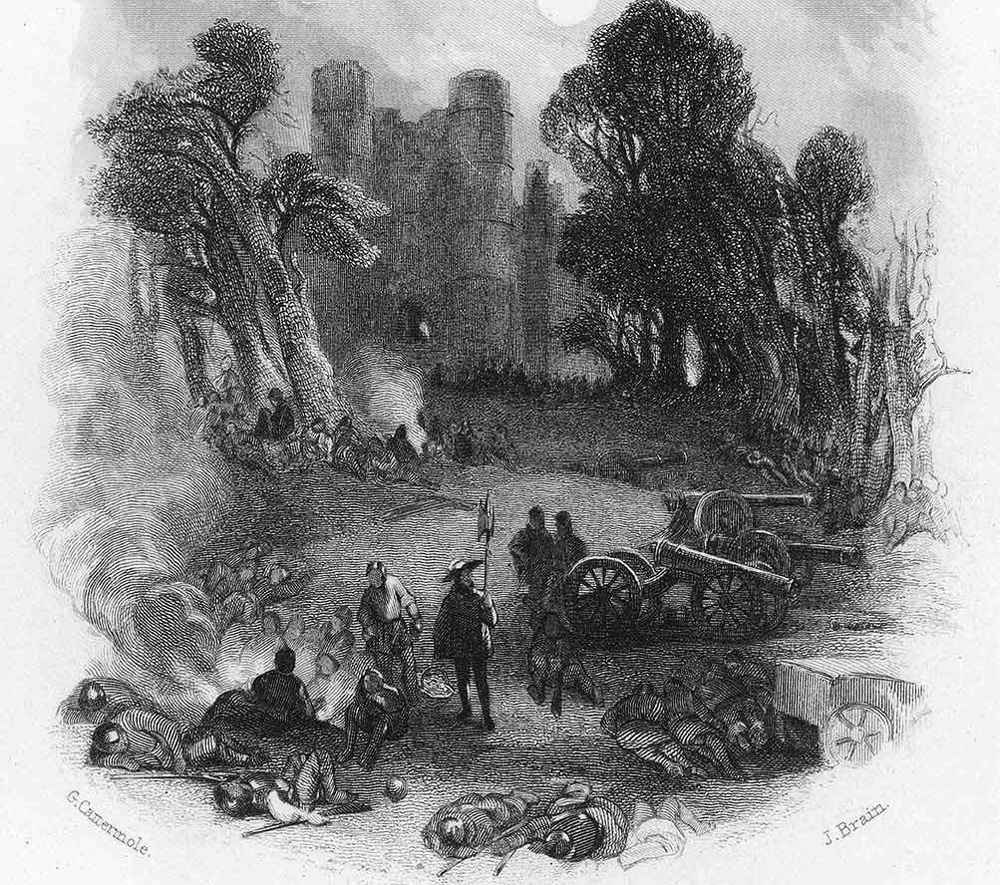

Above left: A 19th-century illustration of the Royalist camp before Donnington Castle in November 1644

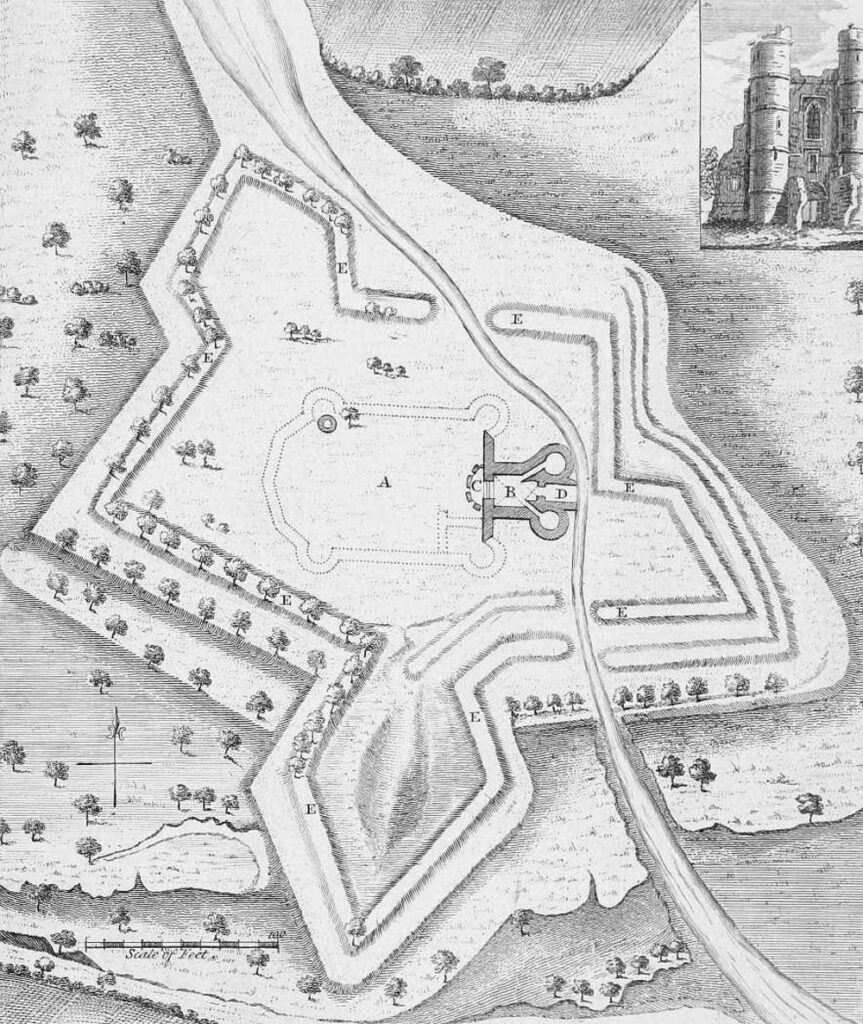

Above right:-A plan of the Civil War earthworks at Donnington, from Francis Grose’s ‘Antiquities of England’, 1756

Donnington Castle was relieved on 21st October, 1644, and King Charles I knighted John Boys for his conduct during the siege and promoted him to full Colonel of the regiment he had previously commanded as a Lieutenant-Colonel subordinate to Earl Rivers, the nominal Governor of Donnington. The king also gave the newly promoted Colonel Sir John Boys an augmentation to his coat of arms of a golden imperial crown or on a blue canton..

Shortly after the relief of Donnington Castle the Second Battle of Newbury was fought under the castle’s walls on 27th October, 1644, and during the fighting the newly knighted and promoted Colonel Sir John Boys led the soldiers from the castle’s garrison to recapture six of the nine guns defending the castle which had been overrun and captured by an attacking force of 800 Parliamentarian musketeers from the Earl of Essex’s regiment. The numerically superior Parliamentary army was unable to defeat the Royalist’s forces and the battle ended in a draw with no side gaining an advantage on the field but the Royalist army ended the day between two Parliamentary forces. During the night the Royalists were able to leave and return to Oxford leaving their artillery, baggage train, and some of their wounded at Donnington Castle, which remained in Royalist hands.

On 9th November the King’s army returned to retrieve the artillery left in Donnington Castle and took up positions around Newbury. Some Parliamentarian commanders, namely Waller, Cromwell and Heselrige were in favour fighting a deciding battle but the Earl of Manchester and his supporters were reluctant to risk defeat and no battle took place. The Royalists were therefore able to resupply the garrison and depart with their artillery, baggage train and wounded.

After the Royalist army decamped the Parliamentarian forces returned to redeploy and recommence their siege of Donnington Castle. The garrison refused to surrender even after the Royalist’s were overwhelmingly defeated at the Battle of Naseby on 14th June, 1645, leaving no functioning Royalist forces in the field. They continued to hold out until April of 1646 when Colonel Boys received a personal order from the King to surrender Donnington Castle, Charles I at that time was about to give himself up to the Scottish army at Southwell. Colonel Sir John Boys and the garrison were allowed to leave the castle with full military honours.

Sir John continued to be an ardent supporter of the Royalist cause and took a prominent part in the Kentish Rebellion of 1648. His persistant anti-Parliamentarian activities led to his being imprisoned in Dover Castle in 1659 and he was not released until February of 1660.

Sir John and Lucy, his first wife, had five daughters but his second marriage to Lady Elizabeth Finch, the widow of Sir Nathaniel Finch and daughter of Sir John Fotherby of Barham, was childless. The Hero of Donnington died whilst serving as Deputy-Governor of Duncannon Fort in County Wexford in Ireland on 8th October, 1664, and was brought home to Bonnington and buried in nearby Goodnestone Church where his memorial can still be seen.

On the left is a photograph of the memorial to Sir John Boys in Goodnestone Church. The inscription reads:

“Underneath rests Sir John Boys late of Bonnington Kent whose military praises will flourish in our annales as laurells and palms to overspread his grave. Dun(gan)non in Ireland may remain a solemne mourner of his funerall; and Dunnington Castle in England a noble monument of his fame the former for the losse of its expert governer the latter for the honour of its g(alla)nt defender.To crown such eminent loyalty and(va)lour ye King Royally added to his antient scutchon a crown. Leaving no other heirs male than man(ly) deeds to keepe up his name his inheritance decended to his three daughters Jane, Lucy, Anne. In his (5)8 yeare, being discharged from his militant state below he was entertained as we hope in that triumphant state above October 8th 1664.”

~~~

Colonels Francis & Robert Hammond

of St. Alban’s Court in Nonington.

Francis and Robert Hammond were younger sons Edward Hammond of St. Alban’s Court in Nonington and were born in 1584 and 1587 respectively. Their mother was Catharine Shelley, who came from a staunchly Roman Catholic family in Surrey and family record that Francis “died a papist at St. Alban’s”. The Hammond brothers were both in their thirties when they joined Sir Walter Raleigh in his ill fated voyage to what is now Venezuela in a futile search for the fabled city of El Dorado that left England in June of 1617.The expedition was a complete failure and Raleigh was arrested on his return to England in mid-1618 and executed at the Tower of London in October of that year on the orders of King James I for breaching the king’s instruction that Raleigh’s expedition must not be involved in any fighting with the Spanish. At present, nothing is known for certain of either Francis or Robert Hammond’s activities for the six years or so after their return to England in 1618.

~~~

Colonel Francis Hammond of St. Alban’s Court in Nonington

Colonel Francis Hammond, born in 1584. A veteran of The Thirty Years War, the Second Bishops War, and the First & Second English Civil Wars. He reputedly fought 14 single combats during his service in The German Wars [The Thirty Years War] & and commanded the forlorn hope at the English Civil War battle of Edgehill on 23rd October, 1642. This portrait hangs in the old Beaney Institute, now the Canterbury Royal Museum and Art Gallery.

By 1624 Francis Hammond, then aged forty, was serving as a captain in Sir Charles Rich’s Regiment as part of “The Mansfeld Levy” in “The German Wars”, now more commonly referred to as the Thirty Years War. An inscription in the top right hand corner of Francis Hammond’s portrait records that during his service in various Protestant armies during “The German Wars” he reputedly fought fourteen single-handed combats.

Colonel Francis Hammond, now around fifty-seven years of age, raised and commanded a regiment under the command of the Earl of Northumberland in the ill-fated Second Bishops War of 1640. Francis was a staunch Royalist and he later served with the Royalist forces in the First English Civil War of 1640-46 where he led a Forlorn Hope of some six hundred cavalry at the Battle of Edgehill in Warwickshire on Sunday, 23rd October, 1642. The Forlorn Hope were the first troops to attack an enemy position and subsequently had only a slight chance of surviving an action, at Edgehill the Forlorn Hope acted as a screen in front of the main Royalist force in an attempt to break up and delay the advance of the Parliamentarian troops.

In the opposing Parliamentary forces at Edgehill was Edward Boys, the younger son of Sir Edwards Boys of Fredville whose land adjoined St. Alban’s Court in Nonington. The young Edward Boys subsequently died of wounds received in the battle at Edgehill, whether or not he encountered Colonel Hammond during the battle is not known, but this emphasises how the English Civil War made enemies of close neighbours and even family members.

Colonel Francis Hammond is believed to have returned to live in Nonington after the defeat of the Royalists and the capture of King Charles I by the Parliamentarians ended the First English Civil War in June of 1646. However, the king’s refusal to accept substantial changes to the his powers and the imposition of unpopular new laws by a Puritan administration led to the Kent Rebellion of 1648 and subsequently to the Second English Civil. Colonel Francis Hammond was one of those commissioned to raise a regiment to fight for the Royalists, initially in the rebellion and then in the more wide spread civil war.

Francis Hammond survived the Second English Civil War and when it ended in another Parliamentary victory he returned to live at St. Alban’s Court where family records state that he was active and “built the kitchin and a little parlour” and lived there until he died “a papist”. There is no record of his burial at Nonington, presumably his having died a Roman Catholic precluded his burial there.

~~~

Colonel Robert Hammond of St. Alban’s Court in Nonington

Colonel Robert Hammond. Served with the Royalist forces in the English Civil War and was shot on the order of Oliver Cromwell while fighting in Ireland. This portrait hangs in the old Beaney Institute, now the Canterbury Royal Museum and Art Gallery.

Colonel Robert Hammond of St. Alban’s Court should not be confused with the Colonel Robert Hammond (1621– 24th October 1654) who was best known for acting as Charles I’s gaoler at Carisbrook Castle from 13th November of 1647 until 29th November of 1648 for which service Parliament voted him a pension. The King’s goaler served as an officer in Cromwell’s New Model Army during the early part of the Civil War and sat in the House of Commons in 1654.

No evidence has yet come to light of Robert Hammond, Francis’s younger brother, having served in The Thirty Years War. However, he did serve as a Lieutenant-Colonel in Francis Hammond’s regiment in the ill fated Second Bishops War of 1640 and later fought for the Royalist cause in the Kent Rebellion of 1648 and the subsequent Second English Civil War.

During May of 1648 the people of Kent petitioned Parliament and when their petition was rejected they rose up in revolt in support of the King. On 23rd May of 1648 Colonel Robert Hammond was commissioned to raise a body of foot soldiers and Colonel Hatton to raise a body of horse, and the following day the two colonels met on Barham Downs, Colonel Hammond with 300 well equipped and turned out foot soldiers and Colonel Hatton with 60 horse troopers. Initially the troops campaigned successfully in the East Kent area against the Parliaments supporters. Colonel Hammond’s forces increased to around 1,000 men and he campaigned throughout Kent and beyond in the Royalist cause. He took part in the defence of Colchester which was besieged by Parliamentarian forces from July, 1648, until the defeat of Royalist forces at the Battle of Preston meant there was no hope of relief for the besieged garrison and they accordingly laid down their arms on the morning of 28th August, 1648. The terms of surrender were that “the Lords and Gentlemen (the officers) were all prisoners of mercy”, and the common soldiers were to be disarmed and given passes to allow them to return home after first swearing an oath not to take up arms against Parliament again. The town people paid £.14,000 in cash to protect the town from being pillaged by the victorious Parliamentarian forces.

Robert broke any parole given to obtain his release as a “prisoner of mercy” when within a year or so he took up duties as the Royalist governor of the castle at Gowran in Co. Kilkenny in Ireland. Cromwell began a campaign against Royalist forces in Ireland in the autumn of 1649 and on 19th March, 1650, Gowran was surrounded by Cromwell’s forces. Colonel Hammond refused Cromwell’s generous terms of surrender which forced Cromwell to deploy his artillery. When the castle walls were breached on 21st March, 1650, Colonel Hammond asked for a treaty, which Cromwell refused to give but he did offer the defending soldiers quarter for their lives which they promptly accepted. The officers were subsequently handed over to the Parliamentary forces and Cromwell ordered the summary execution by firing squad of Colonel Hammond and all but one of the garrisons officers. A Roman Catholic priest who had been chaplain to the Roman Catholic members of the garrison was also captured and hanged.

Cromwell campaigning with the Parliamentary Army, 17th century British School.

Oliver Cromwell referred to the siege and capture of Gowran and the subsequent executions of Colonel Hammond and other garrison officers in a letter written at Carrick on 2nd April addressed to the the Hon. William Lenthal, Speaker of the English Parliament:

“I sent Colonel Hewson word that he should march up to me; and we, advancing likewise with our Party, met “him,” – near by Gowran; a populous Town, where the Enemy had a very strong Castle, under the Command of Colonel Hammond, a Kentishman, who was a principal actor in the Kentish Insurrection, and did manage the Lord Capel’s business at his Trial. I sent him a civil invitation to deliver up the Castle unto me; to which he returned a very resolute answer, and full of height. We planted our artillery; and before he had made a breach considerable, the Enemy beat a parley for a treaty; which I, having offered so fairly to him, refused; but sent him in positive conditions, That the soldiers should have their lives, and the Commission Officers to be disposed of as should be thought fit; which in the end was submitted to. The next day, the Colonel, the Major, and the rest of the Commission Officers were shot to death; all but one, who, being a very earnest instrument to have the Castle delivered, was pardoned. In the same Castle also we took a Popish Priest, who was Chaplain to the Catholics in this regiment; who was caused to be hanged. I trouble you with this the rather, because this regiment was the Lord of Ormond’s own regiment. In this Castle was good store of provisions for the Army”.

Many thanks for the information you’ve so kindly provided. I’ll remove the picture of ‘Ballyseanmore Castle’, and try and find the map you speak of.

only just read your very helpful story of the Hammonds, especially Colonel Robert Hammond who was the commander of the garrison of Gowran Castle during the siege by Cromwell’s troops, but being a Gowran man, and knows its history well, i have to say the picture you have is of ‘Ballyseanmore Castle’ another Gowran castle, and it was captured by Cromwell’s forces too, but its about half a mile from ‘Gowran Castle’, the original is long gone, a new ‘Gowran Castle’ was built in 1812, but there is a map from 1710 of the village of Gowran that shows the castle, there even seems to be a large hole in one section of the illustration, ‘right of centre’, which may have been a “breach considerable”, which Cromwell referred to in his letter. This sketch seems to me as a simple but true depiction by mapmaker of the Castle, maybe he was no artist but i believe he was trying to draw something that was an honest representation, warts and all. You think you can find this map on goggle images, just look closely at the castle, get a loop or good magnifying glass

Victor, many thanks for the comments and the snippet, which is a useful addition to the information I have regarding the Boys family of Fredville and their part in the English Civil War. I was unaware that one of Sir Edward’s sons had died of wounds received at the Battle of Kineton/Edge Hill on 23rd October, 1642. The fact he was a Parliamentarian appears to confirm him to be Edward Boys [Boise, Boyse], the younger brother of Major John Boys of Fredville. The Nonington parish register records the baptism on 14th December, 1606, of “Edward Boise”, the son of Sir Edward, junior, & his wife Elizabeth. He would therefore have been 37 when he died of wounds. I’ll have to try and find out more about him. Thanks again for the snippet.

I enjoyed your reading the various articles as I wrote an article a few years back regarding Sir John Boys,the Royalist and his defence of Donnington Castle during the civil war.

I thought the snippet below regarding a Parliamentary member may be of interest.

Warwick St. Nicholas Parish Register

Buried 22nd Jaunarie 1642/3 Edward Boyse ye sonne of Sir Edward Boyse of East Kent wounded at the Battell at Keynton

Bob, thanks for the post. I think it is William Stupple of Dene (now Denne Hill), an estate and house in the parish of Kingston. Look in Hasted for some detail’s. http://www.british-history.ac.uk/report.aspx?compid=63573&strquery=kingston

A William Stupple was buried at Nonington 2nd June, 1557, presumably the same.You could try looking in Kingston parish records as it’s a large parish and Stupples appears to be a fairly common name in the area records.

If I do find any more info. I’ll let you know.

Regards,

Clive

Clive, your website if most informative and exceedingly interesting.

i have spent a lot of time browsing.

As yet i have not found anymore on William Stupple, Dene of Kyngston, do you think he was

Dene of School or Parish?

I will come over next year hopefully to see Nonington for myself.

If you find anything interesting, i would be most gratefull.

Bob Stupple