Sections on the origins of the names of Fredville and Oxney have been revised.

Fredville:-

Fredville, House and Park: originally a part of the Knight’s Fee of Essewelle. By 1249 Essewelle appears to have divided into Esol (also Esehole & Eshole) and Freydevill, the spelling used in a 1250 legal document. Over the centuries there were many variations in its spelling; Frydewill, 1338; Fredeuyle, 1396; Fredevyle, 1407; Froydevyle, 1430; ffredvile, 1738.

Edward Hasted in the section on Nonington in his “The History and Topographical Survey of Kent”, volume IX, published in 1800, states that Fredville derives from the Old French (OF):freide ville, meaning a cold place, because of its cold, wet, low position.

A more likely derivation is from the Old English (OE) frith or frythe, which in Kentish dialect would have been pronounced “frid”. “A Dictionary of the Kentish Dialect and Provincialisms”,published in 1888, defines a frith as: “A hedge or coppice. A thin, scrubby wood, with little or no timber, and consisting mainly of inferior growths such as are found on poor soils, intermixed with heath, etc”.

John Colking’s Inquisition Post Mortem of 1338 refers to his holdings in “Frydewill, Esole, Nunyngton”.

The original Freydevill manor appears to have been centred around the present Holt Street Farm with the first manor house being built on the old Fredville House site in the early 16th century by the Boys family.

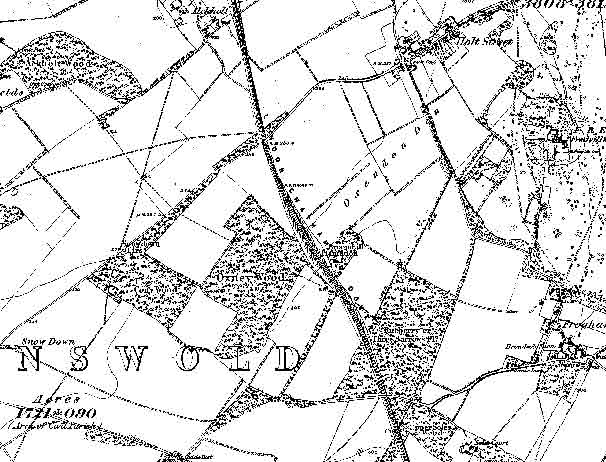

The names Holt Street; from OE. holt, a wood or thicket, and the adjacent Hangers Hill; from OE. hangra, a wooded slope or ‘hanging wood’, indicate a wooded area. Holt Street is bordered to the south-west by Ackholt, oak wood, and to the south by the manor of Oxenden (Oxney), the cattle grazing clearing in the wood, which was heavily wooded in the 12th and 13th centuries. The present Oxney Wood is a densely wooded remnant of this medieval woodland vill’, much of which now lies beneath the old Snowdown Colliery spoil heaps.

The “vill” suffix may derive from “villata”, shortened to “vill” in medieval documents. This was the basic rural administrative land unit which had judicial and policing functions as well as responsibility for taxation, roads and bridges within its boundaries. In this case Fredville would therefore originally have been the vill in or next to the “scrubby” woodland.

In Anglo-Saxon England the vill had been the smallest territorial and administrative unit, a geographical subdivision of the hundred and county. The vill’ had a policing function through the tithing, which was a notional body of ten men, but was usually larger in number, which collectively maintained public order and was responsible for the conduct of its members, being bound to bring any wrongdoers within the tithing before the hundred court. In early Anglo-Saxon England a hundred had consisted of ten tithings. Through the vill’ moot, or assembly, the tithing also organized common projects such as communal pastures.

After the Norman Conquest the vill’ continued as the basic administrative unit, the Domesday Survey of 1086 often refers to vills, and continued to be so until late into the medieval period. Most vills did not make up a manor, or were even contained within a single manor. The vill’ of Frogham [see below] had land mainly in the manors of Fredville and Soles, but also spread into the parish of Barfestone and onto land within the manor of Wingham with manorial rent payable to the relevant lord of the manor.

Alternatively the suffix may derive from the Norman French “ville” ,from the Latin “villa rustica”, which originally indicated a farm, but later evolved into meaning a village, indicating a settlement larger than a hamlet, but smaller than a town which would therefore have made Fredville the settlement in or on the edge of the woodland.

It’s most likely that original “villa rustica” settlement in or beside the “scrubby” woodland eventually evolved into an administrative “villata” as the population increased and then became the manor of Freydevill first referred to in 1249 after the knight’s fee of Essewelle was divided between the two heiresses of Dionisia Wischard around 1218 or so.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Oxney.

Oxney Wood is now in Aylesham and Womenswold parishes, but for centuries the vill’ of Oxenden, as Oxney was originally known, formed part of old Nonington’s southern boundary with Womenswold parish.

Oxinden, 1278; Oxenden 1535; Oxenden, Oxney’s original name, most likely comes from the Old English: Oxena denn; woodland pasture for oxen [cattle]. As can be seen from its description in Archbishop Pecham’s 1280’s survey of the Manor of Wingham, Oxinden was heavily wooded in the 12th and 13th centuries. The present Oxney Wood is a densely wooded remnant of this medieval woodland vill’, much of which now lies beneath the old Snowdown Colliery spoil heaps.

Woodland was a very valuable resource in medieval England, and one of the feudal duties owed by the owners of land in the vill’ of Oxenden to the lord of the manor, in this case the Archbishop of Canterbury, was Pethamlode. This was the duty to deliver cart loads of wood to the over-lord at a specified place and could obviously only be carried out in heavily wooded areas. Woodland then consisted largely of ash and oak which was coppiced at regular intervals on a rotating system to provide a regular supply of timber for building, fencing and a multitude of other purposes. Oak was often cut when a foot or so in diameter to be squared off to make the beams used in the frames of buildings with larger trees used for boards. Medieval Kent had few permanent hedges and fields were divided and crops protected by temporary fences made from stakes with lathes woven in between or “sharn wattles”, large cattle wattles (movable woven wooden panels, also called hurdles) some 9’ x 5 ½ feet in size which were removed after the harvest to allow animals to graze the stubble. Lime and elm were also used in large quantities for domestic and other everyday items.

The Oxendens, a prominent East Kent family, took their name from the vill’ where they held land with manorial duties to the Archbishops of Canterbury’s Manor of Wingham. Thomas de Oxenden was recorded as holding Oxenden in Archbishop Pecham’s survey his Kent holdings of 1283 and in the visitations of 1290-1300.

Soloman Oxenden, ” de Oxenden in Nunnington”, the main land-owner in 1367, married Joyce, the daughter of Alexander de Dene, near Wingham, and they had two sons Allan and Richard. On his death Soloman was buried at Nonington church.

In 1320 Richard de Oxenden, Soloman’s son, took Holy Orders as a Benedictine monk at Christ Church in Canterbury and four years later was ordained deacon by Hamo de Hythe, Bishop of Rochester. The incumbent Prior of Christchurch died, aged 92, on April 6th, 1331, and on April 25th the monks elected Brother Richard de Oxenden, then aged about 30, prior of Christchurch. He continued as such until his death on August 4th, 1338, and was buried in the chapel of St. Michael at Canterbury.

In addition to their Nonington properties the Oxenden’s acquired land near Wingham and married into local families holding land at Ratling and Goodnestone.

Edward Oxenden of Dene near Wingham 1501 was appointed Warden of Cruddeswood Park, later Curleswood Park, a deer park belonging to the Archbishop’s of Canterbury a mile or so to the north-west of Oxenden. A large part of the deer park is now covered by the mining village of Aylesham..

In 1510 John Oxenden of Nonington left bequests to Nonington church and requested to be buried in the church-yard there.

Oxenden’s eastern boundary with Soles and Fredville manors was formed by Rubberie Downs, called Rowbergh in 1415, then open downland which stretched from the Roman Road (the North Downs Way) to the present Nightingale Lane, part of which are now occupied by Rubberie and Little Rubberie Wood. Oxenden’s northern border with Fredville appears to have been Nightingale Lane.

Various documents from the 16th and 17th centuries refer to a house and buildings on Ruberries and the 1626 Boy’s marriage document refers to a house, buildings and three acres of pasture land occupied by John Mundaie near Rowberries.

People appear to have lived at the ancient manorial settlement until at least the 1660’s, the church register for nearby Sibertswold (Shepherdswell) parish records the wedding on October 4th, 1667, of Richard ffryer of Sibertswold and Elizabeth Sayers of Oxney, but this is the last known written evidence of habitation.

The bank between Oxney Barn Forestall and the railway line was referred to on old parish maps from the early 19th century as Oxney Barn Bank, which later became known as Plane Tree Bank. Until comparatively recent time the majority of this bank was unwooded, as can be seen on the 1839 tithe map.

There are now no visible traces of any of the ancient buildings but the names Oxney Barn Forstal, Oxney Barn Field, and Oxney Barn Wood on the 1839 Nonington parish tithe map [see below] provide some evidence to the probable site of the buildings.

The reference to Oxney Barn Forestall on the 1839 Nonington tithe map indicates it was the location of ancient farm or possible manorial buildings as a forestall was the area in front of, or leading to, a farm or manor house. This would have been the administrative centre of the vill’. Oxney Barn most likely refers to agricultural buildings in use after people had ceased to live there.

Reference to Oxney Barn in the forestall, field, and wood names on the 1839 map also indicates that a substantial building existed there perhaps only a generation or so before 1839 with possibly one or more of the buildings referred to in the 1626 Boys document possibly in use as a barn into the early 19th century.

The 1839 map was drawn up using existing, and often factually obsolete, land-owners property maps and documents, whereas the later 1859 parish map was drawn up from a full survey.

Oxney Wood became part of the Woolege Farm estate in Womenswold parish and came into the possession of the trustees of Sir Brooke Bridges of Goodnestone in the 1750’s and was later sold to the Plumptres of Fredville, possibly at the same time as the Holt Street estate. Oxney Wood is still part of the Fredville estate owned by the Plumptres.

After the Second World War a plantation of fir trees was planted on the lower western edge of the bank which became known as Oxney Firs.

In addition to Oxenden, Wingham Manor had another 244 acres of woodland a mile or so to the west of Oxenden at Curleswood, then in Nonington parish and a mile and a half or so to the south at Woolege in Womenswold parish where the Woolege Woods stood until well into the 20th century when they were gradually cut down from nearly 300 acres to the small area which remains to-day.